Many think of big leaps in quantum physics as something related to the first half of its centennial history, but that is not the case. In fact, a big breakthrough came about around 20 years ago, when we were first able to create a fermionic condensate. The scientist bringing us this beauty of Nature was Deborah S. Jin.

Dr Jin joined JILA in 1995, after completing her PhD at the University of Chicago. That was a momentous year at JILA, as Eric Cornell and Carl Wieman had just engineered the first Bose-Einstein condensate in a lab.

To better understand the context of this breakthrough, let’s take a step back and look at these condensates.

We are used to thinking of states of matter as three categories: solid, liquid, gas. But there is much more out there when it comes to different states. I wrote a few posts about a special one, superconductivity, which turns out to actually be a special form of a Bose-Einstein condensate made of electron pairs, also known as Cooper pairs.

A Bose-Einstein condensate is a macroscopic quantum state in which all participating particles, which belong to the category known as bosons, share the same collective wavefunction, behaving as one single quantum entity.

There is another category of particles though: fermions. While bosons are social and tend to occupy the same quantum state, meaning they all have the same set of quantum numbers, or properties, like position, spin, energy and so on, fermions are anti-social and strictly avoid each other, always differing by at least one of the quantum numbers describing their state. This is known as the Pauli principle.

The division between bosons and fermions is quite straightforward, as it is intrinsic to whether a particle has a half-integer (for fermions) or integer (for bosons) spin. This distinction dictates their statistical behavior, with bosons following Bose-Einstein statistics and fermions obeying the Pauli exclusion principle.

So, as one can see, the Bose-Einstein condensate (BEC) seems to come naturally from the bosons wanting to be all together: at low enough temperatures, all bosons will occupy the same quantum state, naturally creating a condensate. On the other hand, anti-social fermions will not naturally condense onto the same state, even at very low temperatures. The only way for fermions to form a condensate is to first form pairs, similar to the Cooper pair formation in superconductors.

Besides the clear limitation imposed by the physical nature of these anti-social particles, there was another, more technical, issue to solve: fermionic condensates need extremely low temperature, much lower than their bosonic counterpart.

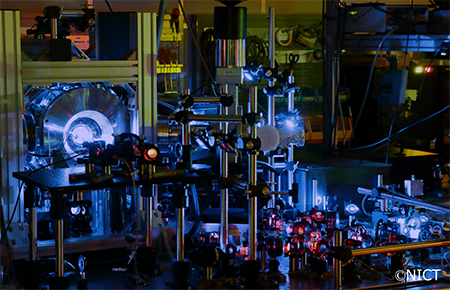

With her physical insight and the expertise developed at JILA studying Bose-Einstein condensates and ultracold fermion gasses, Dr Jin and her team prepared an experimental setup that cooled down atoms on two separate magnetic sub levels, restoring their ability to collide and allowing researchers to use a well-established cooling technique known as evaporative cooling, the same technique that had led to the first BEC realisation.

By cooling down pair of atoms, Dr. Jin and her team were the first to report on another groundbreaking discovery: the BCS-BEC crossover. BCS stands for Bardeen-Cooper-Schrieffer, the theory describing conventional superconductors. The differences between these two states might appear subtle, but they concern the fundamental behaviour of the atomic pairs. In the BCS case, atoms form Cooper pairs, which are large and weakly bound. On the other hand, in the BEC case, the condensate consists of tightly bound molecules of fermions. Another difference is in their quantum behaviour: the BCS state exhibits superconducting behaviour, with strongly overlapping fermion pairs. The BEC state shows characteristics of a true condensate of bosonic molecules.

This is called a crossover rather than a phase transition because the transition between the two regimes occurs smoothly as interactions are tuned, without a singular point marking a phase boundary. Moreover, the parameter tuned in this change is not temperature, but the interaction between atoms, which can be controlled experimentally using Feshbach resonances.

Building on this success, in 2008, she and her colleague Jun Ye produced the first stable ultracold gas of KRb (potassium-rubidium) dipolar molecules. Their new approach turned the problem on its head, as they took an ultra cold gas of atoms and transformed its atoms in dipolar molecules with the use of magnetic fields and laser beams.

Dr. Jin’s groundbreaking research opened up the door to a whole new field: fermionic quantum simulators. These quantum simulators allow us to study fundamental problems in quantum chemistry and condensed matter physics with the utmost precision and control. In fact, fermionic quantum simulators provide a natural framework for studying strongly correlated fermionic systems, often outperforming qubit-based approaches for such problems.

Due to her seminal work, Dr. Jin was often mentioned as a candidate for the Nobel Prize, though never a recipient, perpetuating a pattern of overlooking women’s contributions in the field of physics.

Deborah Jin’s groundbreaking work not only redefined our understanding of quantum matter but also laid the foundation for modern quantum simulation. Her pioneering experiments continue to shape research in ultracold physics, proving that her legacy, like the fermionic condensates she first created, will persist. Beyond her scientific achievements, she set an example of mentorship and balance, proving that excellence in physics does not have to come at the expense of life outside the lab.

Leave a comment