Bridging Disciplines Before It Was Mainstream

Interdisciplinary might seem like a relatively recent concept, but one pioneering scientist was already bridging disciplines at the dawn of quantum mechanics: Hertha Sponer.

From Teacher to Trailblazing Physicist

Born in German Silesia in 1895, Sponer followed the only path to higher eduction then available to women in Germany. She completed a training as an early childhood educator and primary school teacher. Then, in 1917, she completed her secondary school diploma at the Realgymnasium. Only then was she allowed to enrol at university, first for a year in Tübingen and later in Göttingen.

She was part of the trio made of the first women to complete a PhD in physics and the Habilititation, the right to teach, in Germany. Together with her, two other giants of quantum physics: Lise Meitner and Hedwig Kohn. I will be writing about them in the upcoming months.

Her 1920 thesis “On the infrared absorption of diatomic gasses” is one of the stepping stones in the field of band, or molecular, spectra.

Decoding Molecular Spectra

The use of the word spectrum had been introduced by Isaac Newton to describe the splitting of white light into the different colours when passing through a prism. It was quickly adopted in the context of optics and light studies. Several contributions based on pure observation came in the 1800s, including diffraction grating and the first spark-emission spectroscope. Already in 1826, Talbot reported how different salts would produce different coloured lights when placed on a flame. A bit later, in 1859, Kirchoff and Bunsen had realised that spectral lines were unique to each element. This realisation marked the beginning of atomic spectroscopy and brought to the discovery of new elements, including cesium, rubidium, and thallium.

![infographic for atomic vs molecular spectroscopy. Atomic spectroscopy includes two spectra, one for Helium with 5 visible lines, one for Sodium with many more visible lines. The spectra are coloured depending on their wavelength and shown against a black background. For molecular spectroscopy, the absorption spectrum of the manganese complex [Mn(H₂O)₆]²⁺ is featured in black and white.](https://clioagrapidis.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/atomic-spectra.png?w=819)

Quantum Mechanics and the Language of Light

However, a real physical explanation for the different spectral line series seen in different elements was not possible until the advent of quantum mechanics. This theory posed that electrons in atoms could only occupy orbitals with quantised energies. Moreover, an electron jumping from a state with higher energy to one at lower energy emits a photon (light) with energy equal to the difference between the orbitals. This photon, in turn, will have a frequency (and a wavelength) defined by the aforementioned energy difference.

Translated, it meant that the different coloured lines saw depending on the analysed elements were a direct view into the electronic structured of that specific atom. Hence, they had to be unique for each element, as already postulated by Kirchoff and Bunsen.

The Challenges of Molecular Spectroscopy

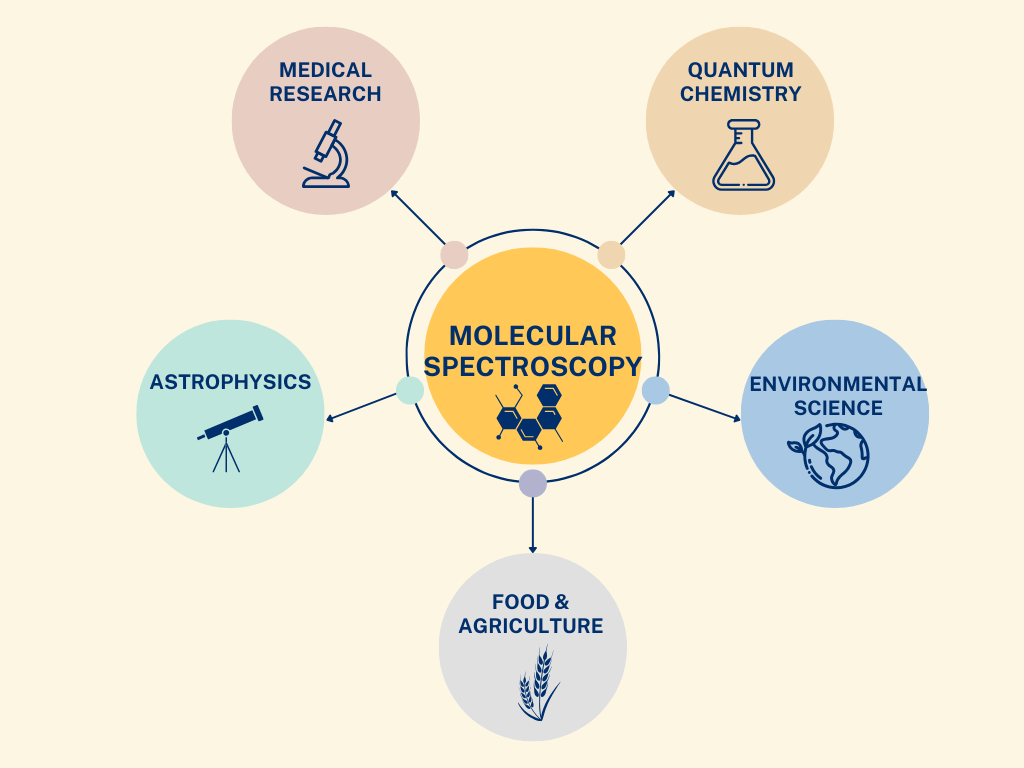

Atomic spectroscopy is characterised by discrete lines, but applying the same technique to molecules brings a number of complications. For starters, the measured spectra are band spectra, groups of closely spaced lines. Molecules are composed of more than one atoms and have access to more degrees of freedom, such us rotations and vibrations. These added properties lead to splitting of the energy lines seen in atomic spectra, resulting in way more lines and less separation between them.

A method for molecular dissociation energy

Sponer was not only able to measure high quality spectra, but also to interpret them correctly. Together with Raymond Thayer Birge, she developed the Birge–Sponer method to calculate the dissociation energy of a molecule from its vibrational spectrum. This is the energy needed to break apart the molecule into single atoms, giving us information on the stability and safety of the molecule itself.

Forced to Leave: The Cost of Being a Woman in Science

By 1932, she had already published 20 papers and had been granted an extra-ordinary (Ausserordentliche) Professor position, but Hitler’s rise to power meant her achievements had no relevance anymore. The reason? She was a woman, and Nazi ideology did not include women in universities. Rather, they expected women to stay home and support their husbands. Kinder, Küche, Kirche (“children, kitchen, church”) was the slogan chosen by the Nazis to describe a woman’s place and expectations.

Sponer soon understood that she would have to move away from Germany if she was to keep pursuing her scientific career. In 1934, she moved to Norway and held a Guest Professor position in Oslo. The final trip in her academic career journey was to Duke University. She arrived there thanks to a special program ran by the Emergency Committee with the purpose of employing displaced scholars who had fled Germany due to racial or political persecution.

A New Start in Exile

If the administration at Duke University had expected someone who would mostly be involved with women undergraduate students, they must have ended surprised. Sponer immediately showed how dedicated she was to research, publications, and professional discussions and meetings. She built her lab in the subbasement, including pedestal built on separate foundations to ensure stability against vibrations. This seemingly peculiar placement ensured a quiet space with the almost no temperature fluctuations, perfect for her experiments.

Pioneering Interdisciplinary Science

A pioneer of interdisciplinary research, Sponer worked at the intersection of physics and chemistry. She described her field as Chemical Physics and was editor in the Journal by the same name for several years. Later, her work was deemed part fo the field of Physical Chemistry, though her methods were always those of physics.

Thanks to her experimental acumen, Sponer confirmed many early quantum mechanical predictions in her lab. One of her mosti important publications are the two volumes of Molekülspektren (Molecular spectra). The first volume is a monograph enclosing the current theoretical and experimental knowledge at the time, the second includes all available data in ordered tables for easy access.

Recognition and the Limits of Categorization

Her work was fruitful and recognised by her peers, as demonstrated by the many collaborations with respected scientists, as well as invitations and visits to other institutions. However, she worked in close collaboration with James Franck, who later became her husband, so that some came to doubt her independence and creativity in research. Moreover, her field was considered as applied, rather than fundamental. Her interdisciplinary approach made it harder for her work to gain full recognition, as it did not fit neatly into the traditional categories of physics or chemistry. While continuously confirming theoretical predictions, it did not give rise to controversy or groundbreaking discoveries that could grab the attention of the wider public.

Nonetheless, her human and administrative skills were already clear at the time. Sponer showed all the qualities of an efficient institute director. She supervised several master and PhD students while organising research work and visit, often surpassing her male colleagues in these tasks and qualities.

From Exile to Excellence: What Hertha Sponer’s Story Teaches Us Today

The story of Herta Sponer is the story of someone being forced out of their institution based on their gender. A talented individual forced to move away from her country, who found a new home in the place that allowed her to pursue her vision and use her abilities.

With the latest cuts to scientific research carried out by the Trump administration, some questions easily comes to mind: how many great minds will take the opposite route back to Germany, and, more broadly, Europe? How many will be forced on different paths due to the circumstances? How much knowledge will be lost in the process?

Leave a comment