Crisis often brings opportunity — but only to those ready to act. With U.S. science agencies unable to disburse grants due to political gridlock, the EU has an unexpected opening. The question is not only whether it can attract displaced researchers, but whether it is ready to become a true global hub for research and innovation. While many might not wish for the circumstances to continue as is or even deteriorate, the EU is given an opportunity to attract top-talent and build the science of tomorrow.

This opportunity seems to be only growing bigger in face of the events following the first two months of the second Trump administration.

From Concern to Crisis: How U.S. Science Is Being Undermined

Already in the first two weeks of its second term, President Trump signed a series of executive orders that were deemed by many as “anti-science”. From leaving the Paris Agreements, to halting meetings and grant reviews at the National Institutes of Health and the National Science Foundation, the first moves of this administration scared some but were seen as transitional by others.

But recent decisions have shown that these concerns were not just alarmist.

Funding for the NIH has been slashed, overhead costs for universities are no longer reimbursed, and Columbia University has faced a series of targeted cuts — moves some interpret as an attempt to make an example of a “woke and left-wing” institution. While these measures are often framed as a crackdown on elite academia, their impact reaches far beyond the Ivy League, hitting Republican states and smaller institutions just as hard.

But what does this all mean for scientists? Several aspects of a researcher’s job and its security are now affected.

How the Cuts Impact Researchers

Before these recent changes, winning a call for a grant, often a very competitive one, meant you could be sure you would have the funding to conduct your research for the next three to five years. Unless serious misconduct occurred, ongoing funding was secure. And even in those extreme cases, institutions could remedy the situation and keep applying for those same programs.

Now, your research topic can determine whether your project is allowed to continue—or abruptly terminated—even after funding has been approved. This does not only affect the person who wrote and is managing the project, but also, and most predominantly, people hired for that project.

Early career researchers are particularly affected by these cuts, with scholarships and stipends being revoked from one day to the other, professors scrambling to find alternative sources of income for their students and postdoctoral researchers, and those same young scientists struggling to secure positions as teaching assistants to economically support their research.

Institutions Under Pressure: Harvard, Princeton, and Beyond

Cuts are not targeted only at specific topics, but at some chosen institutions as well. Just this month, Harvard defied demands from the US government and was punished with the freezing of $2.3 billion in federal funds.

With the recent announcement of further cuts to Princeton’s climate research, NOAA (National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration), and NASA’s science program, the situation for science and research in the US seems more and more dire.

As the former NOAA administrator Rick Spinrad said “By making a complete divestiture in science and in our research enterprise, we are basically saying we are not interested in improving our quality of life or our economy”.

A Brain Drain in the Making? Three in four U.S.-based researchers are considering leaving

These cuts, coupled with constant political pressure, have fostered an atmosphere of uncertainty within the research community. Many students and researchers are now considering relocating. In a recent poll, around 75% of respondents admitted to wanting to leave the US. With the most recent events unfolding, this percentage might be even higher now.

Europe’s Moment: building the Research Hub of Tomorrow

The need-driven desire of this scientific talent to relocate is an opportunity for Europe. With its roster of internationally recognized universities and its commitment to research funding as represented by the Horizon Europe and other programs, the EU can benefit from the current uncertainty in the US and offer its facilities to researchers burned by the unprecedented budget cuts. For all that, some bureaucratic hurdles could halt all of European goodwill, as visa and residence permit issues are not new to relocating scientists.

Indeed, the European Commission wants to offer refuge to US-based scientists affected by the new research policies. The European Commissioner for Startups, Research and Innovation Ekaterina Zaharieva told EU lawmakers this month that “Europe can and should be the best place to do science […] a place that attracts and retains researchers, both international and European.”

This statement follows an undated letter urging the Commission to bring over talent from abroad “who might suffer from research interference and ill-motivated and brutal funding cuts”. While the letter did not openly cite the US, the implication was clear, stating “The current international context reminds us that freedom of science can be put at risk anywhere and at any time”. This letter was signed by 13 countries: France, the Czech Republic, Austria, Slovakia, Estonia, Latvia, Spain, Slovenia, Germany, Greece, Bulgaria and Romania.

Moreover, Zaharieva announced that the Commission would enshrine freedom of scientific research within EU law together with increasing the financial support offered by the European Research Council (ERC).

Currently, researchers relocating from the US or another third country can apply for €1 million beyond the usual maximum grant amount. To increase the pull factor, this will go up to €2 million.

There is an historical parallel to this foreseen movement of scientific minds from one side of the Atlantic to the other. Almost a century ago, Nazi-Fascism and WWII led many brilliant scientists to cross the ocean from Europe to the US to find asylum and continue their work. This contributed to shifting the research center of excellence from the old continent to the States.

National Efforts: France, Belgium, Spain, and Germany Step Up

Now, the opposite might happen, if Europe acts on its promises and builds an environment conducive to research and technology development. As Yasmin Belkaid, the director of the Pasteur Institute in Paris, told the French newspaper La Tribune, “You could call it a sad opportunity. But it is an opportunity all the same”. She announced her Institute is working to recruit American experts in infectious diseases and the study of origin of the disease.

The Pasteur Institute is not the only French institution setting up programs to attract researchers who need or want to leave the US. The Aix-Marseille University was among the first to announce its plan, called Safe Place for Science. In the first call for applications, it allocated €15 million to offer employment contracts to about 15 researchers for three years plus up to €600k research budget, together with relocation assistance. The call was answered by more than 100 scientists from institutions including NASA, Yale, and Stanford.

But France is not the only country who has set up programs to attract American-based researchers. The Vrije Universiteit Brussel, in Belgium, opened 12 postdoctoral positions for international researchers, with a focus on those currently affiliated with an American lab. Its rector, Jan Danckaert, released a statement saying “American universities and their researchers are the biggest victims of this political and ideological interference. They’re seeing millions in research funding disappear for ideological reasons.”

Just over the border, in the Netherlands, Education Minister Eppo Bruins proposed a fund to attract international academics, inspired by similar initiatives in France, Spain, Germany, and Belgium. But despite the ambition, no budget has been secured: a motion to support it failed in Parliament. Universities, says Ruben Puylaert of Universities of the Netherlands, “cannot do this alone” — and without coordinated European funding, the plan remains wishful thinking.

Spain was also among the first countries to open up its academic doors to scientists looking to relocate. By making use of its Atrea (Attract) program, it is already closing deals with at least eight scientist looking to relocate their research. In 2024, €30 million were allocated to this program and the Spanish Ministry of Science, Innovation, and Universities recently announced an increase of €15 million to that budget for the current year, bringing it up to €45 million. Within Spain, the autonomous region of Catalonia also announced a program to hire 78 high-level researchers currently working in the United States.

Germany is also expected to follow suit. A recent op-ed in Der Spiegel is urging country’s leaders to target 100 bright minds for Germany. The city of Berlin has already established a special funding program supporting local research institutions in offering options for those seeking to relocate. The local senate underlined how they want to provide researchers with a place where they can be free to carry on their research in a unique environment.

The Visa Hurdle: A Major Threat to Europe’s Research Ambitions

Altogether, over €100 million has already been mobilized across Europe to host displaced U.S. scientists. And while all of these programs seek to award funding to talented researchers, getting funded is not a straightforward road to Europe. As the case of physicist Gilly Elor shows, visa issues can mean a change of plans. She received confirmation of being awarded a grant within the Spanish Atrae program (see above) in November, but just four months later she was told there were issues with her visa application. The granting agency and her perspective hosting institution did not help in solving the issue. Now, she might have to stay in the US.

Resolving immigration hurdles has to be a priority for the Commission in order for all of these planned actions to succeed. Commisioner Zaharieva is indeed discussing the issue with her counterpart in charge of internal affairs and migration, Magnus Brunner. Reducing the need for general paperwork when carrying out administrative tasks related to research like buying equipment could also make EU-based institutions more attractive. Especially in light of Trumps’ tariffs making it very hard for scientist to buy the necessary tools for their research.

The Bigger Picture: Economic and Scientific Returns for the EU

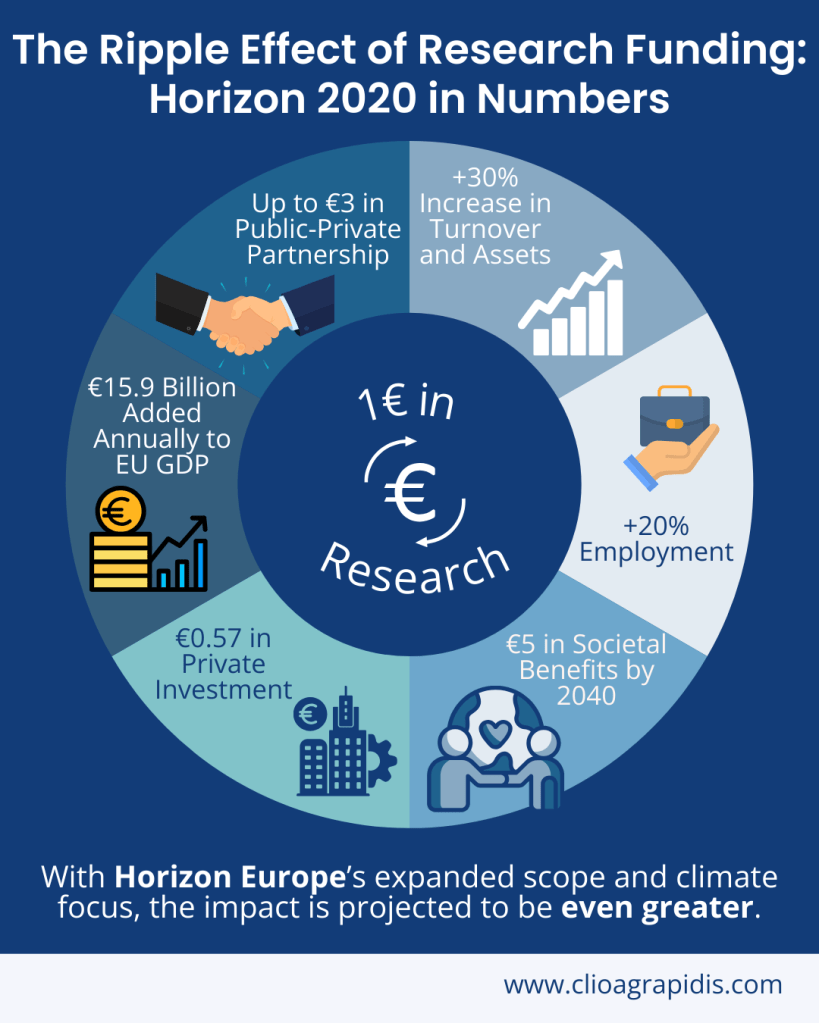

Increasing the research budget to attract relocating scientists is not only an act of altruism. For every euro spent, several more follow from the private sector, and economic returns are substantial. The Commission’s previous funding program, Horizon2020, drove a 20% increase in employment and a 30% rise in turnover/assets. It added €15.9 billion annually to the EU GDP, projected to a total of €429 billion by 2040. For each euro invested, it generated €5 in societal benefits by 2040, while also seeing an increase of €0.57 in private investments, rising to €3 in public-private partnerships. With its broader scope and special attention to climate-focused missions, the current funding program, Horizon Europe, aims to amplify this impact.

Will Europe Deliver on Its Promises to Scientists?

On Monday 5th May 2025, France president Macron and European Commission president von den Leyen publicly announced their invite to US- based researchers: “Choose Europe for Science”. The event took place at La Sorbonne, and speeches were full of promises to science and how Europe has always supported science. But while President Macron is promising €100 million in investment to attract foreign scientists, what will be of those already in France? His administration recently cut €1.5 billion to French universities. How will researchers on mostly temporary contract find new opportunities if universities do not have money for salaries? And while Italian president Meloni took it as a perjury that the event took place in France rather than Italy or Brussels, what can Italy teach in terms of research investments? With its mere 1.37% of the GDP invested in scientific research, it is below OSCE averages since years. On the other hand, France invests 2.19%, Germany 3.3% and Sweden up to 3.6% of their GDP.

While Europe has a one-of-its-kind international funding scheme and a history of support for science, single countries are still holding back in seeing it as an investment. Unless structural issues are addressed, some may see their stay as temporary. What happens next? Will they stay, or will they go back when a new administration enters the White House, possibly reversing some of the current policies? Only time will tell.

Leave a comment