I clearly remember the day I decided I wanted to specialise in condensed matter physics. It was during the last year of my bachelor studies. As we often did when we had questions on exotic (to us) physics concepts, me and my two study buddies went to ask Prof. Flavio Toigo for enlightenment. The main reason behind our visit: a recent publication about observing magnetic monopoles.

As young students, we were baffled. We had taken the General Physics 2 class with Prof. Toigo. Most of this standard physic course in Italian universities deals with classical electromagnetism. One concept that is repeated over and over again, even at high school level, is the following:

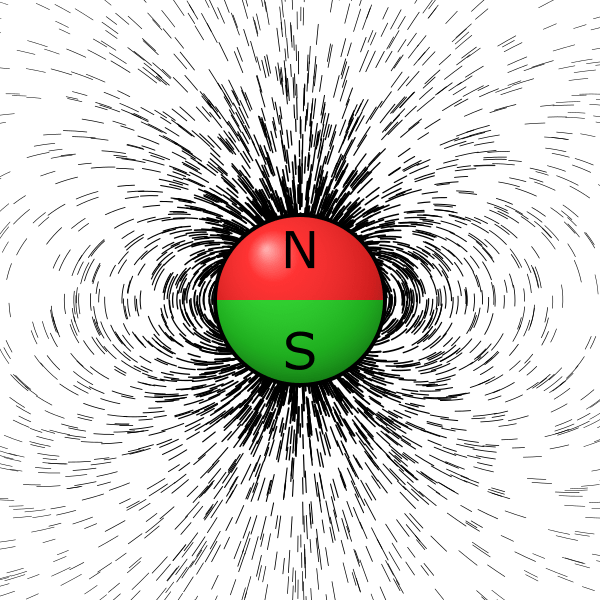

A magnet will always have two poles (north/south)

Or, in other words

Magnetic monopoles are not allowed by Maxwell’s laws

Maxwell’s law are the four equations that encompass all of the relevant phenomena happening in classical electromagnetism. They describe how the electric and magnetic field behave and how they influence each other. The formula prohibiting magnetic monopoles is often referred to as Gauss’s law for magnetism. It states that the flux of the net magnetic field over a closed surface is zero. Visually, this corresponds to always having the same number of magnetic field lines going in and out of the closed surface. Hence, no magnetic charge can build up at any specific point. Practically, this means the south and north poles of a magnet have the same strength. If we cut a magnet in two, each piece will still have two distinct poles. Cutting further will only create smaller dipolar (having two poles) magnets.

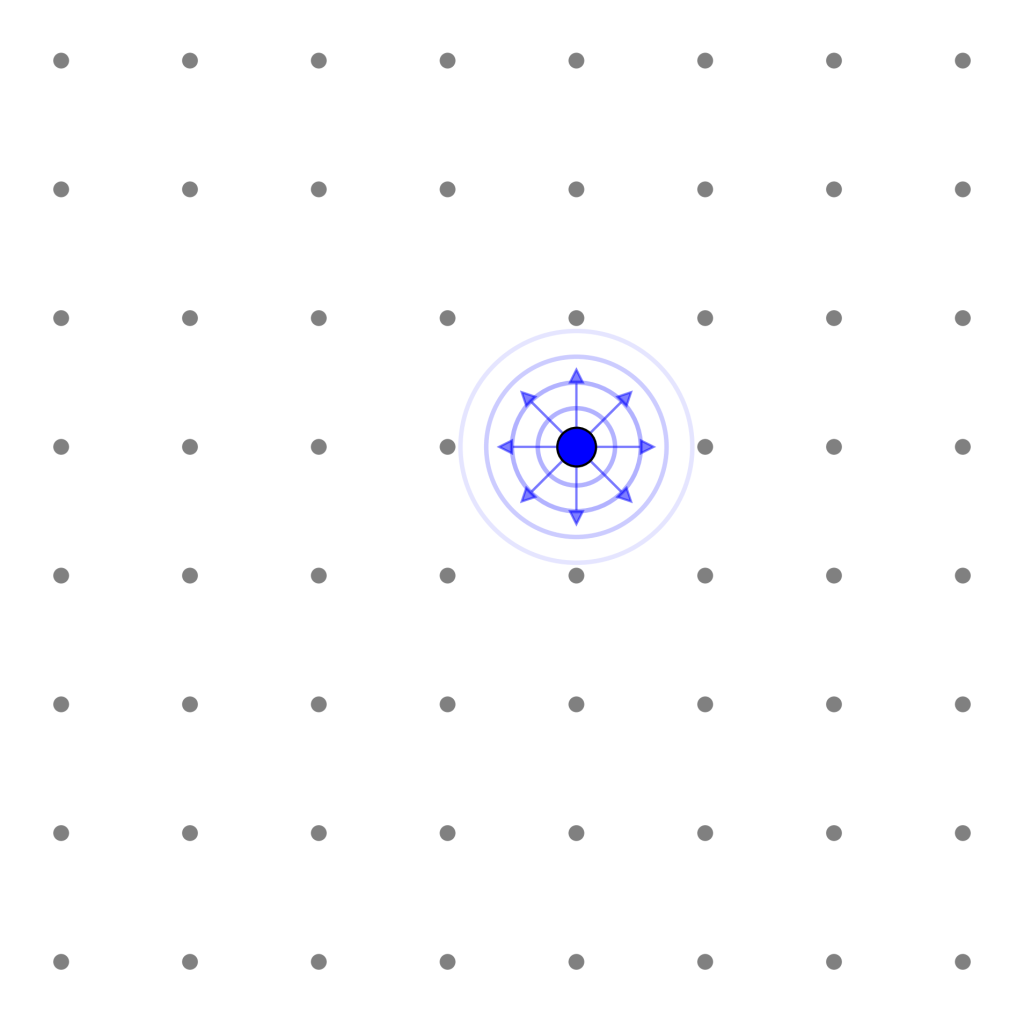

On the other hand, a magnetic monopole would have a net “magnetic charge”, either south or north.

At the quantum level, the electron also acts as a magnetic dipole. However, quantum theories of magnetism predict the possibility of magnetic monopoles. Indeed, Paul Dirac proposed that if at least one magnetic monopole exists in the universe, then electric charge must be quantized. This latter observation is true, so one might expect magnetic monopoles to exist somewhere in the universe. Alas, we still have not been able to measure a single magnetic monopole as a fundamental quantum particle.

So, how did my friends and I find ourselves in front of our mentor with big questions marks on our heads?

I believe this is due to poor reporting of scientific findings for the general audience. Newspapers were flooded with headlines like “Magnetic monopoles finally observed.” As physics students, we weren’t buying it. But, as yet inexperienced physics students, we also didn’t know how to find the answers ourselves.

And so here we were, eager to here a reasonable explanation, waiting for illumination and hoping what we had just studied last semester was still valid few months later.

With a sigh and a barely suppressed laugh, Prof. Toigo gave us this answer

They did not observe magnetic monopoles. They observe something that behaves like a magnetic monopole.

This “something” is what is known as a quasiparticle, a concept I will dive into soon but will briefly explain here. In solid-state systems, a huge number of atoms interact with each other. The number is so large that solving the equations describing the interactions between all the atoms is practically impossible. Therefore, we come up with models that retain only the fundamental aspects of the material.

Very often, this collective interaction results in an emergent quasiparticle: an entity that behaves like a particle, following the dynamics dictated by quantum mechanics, but that cannot exist outside of this collective behavior. There is a full zoo of such quasiparticles, and I will introduce them later, but for now, let’s go back to the answers that blew our minds.

The concept of a quasiparticle is hard to grasp. That’s why we were still as confused as when we entered the office. What is something that behaves as a magnetic monopole? Why is it allowed? Are Maxwell’s equation still valid?

Prof. Toigo quietly answered all of our questions, reassuring us that, yes, Maxwell’s equation were still valid, we did not have to restudy the full classical electromagnetism class. He introduced us to the concept of quasiparticles and the beauty of solid state systems. And then, he shared what made me choose my research path:

People are still trying to look for Majorana particles. Neutrinos probably ain’t it and it is very unlikely we will find a fundamental particle that is a Majorana particle. But you know where Majorana (quasi)particles can exist? In condensed matter systems.

And that was it. At the time, I was obsessed with Ettore Majorana and Majorana particles and neutrinos. Like many others, I had enrolled in physics thinking of quantum mechanics, fundamental particles, CERN, and trying to understand the model that governs the universe. I thought that was all physics research was about. Instead, a patient professor with an open-door policy opened a gate to a new land of complexity and unexpected behavior. I am forever grateful for that afternoon.

Leave a comment