Half the globe is experiencing winter season and, as we plan our winter vacations and dream of snowy mountains, I am thinking of the very beginning of another subcategory of physics I belong to: low temperature physics.

The end of the 19th century saw a freezing rivalry between Dutch physicist Heike Kamerlingh Onnes and Scottish chemist and physicist James Dewar. This race seemed to be won by the latter as he is the first to liquify hydrogen in 1898. A persistent character, Kamerlingh Onnes sets up to liquify helium. A goal he achieves in 1908, 10 years after hydrogen liquefaction. Not only this, he goes on to reach the coolest temperature ever achieved on Earth until then: 1.5K (Kelvin), or -258.15˚C (Celsius degrees).

Portrait of Dutch physicist Heike Kamerlingh Onnes, the first observer of superconductivity. He was also known as “the gentleman of absolute zero”. His motto was “Door meten tot weten” (“Knowledge through measurement”).

Rather than keeping his attention on reaching lower temperatures, he focused on building up new machines and equipment to store and work with it. He built up a real low temperature physics lab and was ready to start answering open questions, like what happens to electron in conductors near absolute zero (0 K, or -273.15˚C).

A conductor is a material that allows for an electrical current to flow in one or more direction. Pure metals and metallic materials are example of electrical conductor. Some believed that, at absolute zero, electrons in such materials should come to a halt, making the electrical current disappear. Kamerlingh Onnes had a different theory, though. He expected the conductivity to continuously decrease and eventually disappear at zero temperature.

Now, thanks to his liquid helium setup, he could finally test this idea.

In April 1911, Kamerlingh Onnes submerged a wire of solid mercury in a helium bath. His choice of mercury was deliberate: he was sure any impurities in his sample could alter his observation, and he knew how to produce very clean samples of mercury or gold. His setup measured electrical resistance—the property that determines how hard it is for electrical current to flow through a material. More resistance means a tougher time for the current to move; less resistance, an easier flow.

The experiment began as expected: resistance decreased as the temperature dropped. Then, at a chilling 4.2K (-268.90˚C), something astonishing happened. The resistance didn’t just decrease—it vanished entirely. Kamerlingh Onnes was stunned. Could it be an error? Something wrong in the experimental setup or the measuring equipment? He repeated the measurement several times, but the results were always the same: at 4.2K, resistance disappeared.

Sure of his observations, he clearly understood the scope of his discovery. He writes “Mercury has passed into a new state, which on account of its extraordinary electrical properties may be called the superconductive state“. This was no minor anomaly; it was a new state of matter. And had he chosen to measure gold instead of mercury samples, this discovery would have eluded him.

The term “superconductivity” came naturally to Kamerlingh Onnes. Resistance and conductance are opposites: high resistance corresponds to low conductance, while low resistance means high conductance. Zero resistance, then, represents an ideal conductor—a superconductor.

But the story does not end here.Physicists were about to discover an unexpected behaviour in these materials. Something previously unimagined.

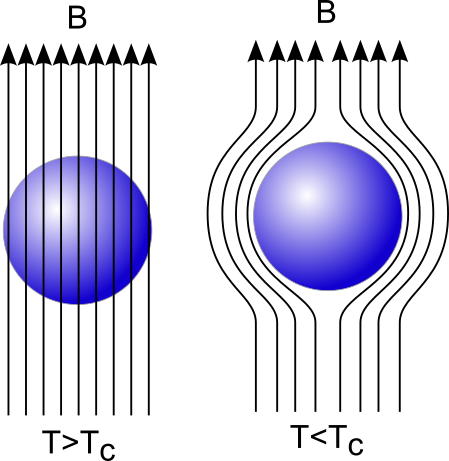

In 1933, more than 20 years after the first observation of the superconducting state, Meissner and Ochsenfeld uncovered another unforeseen behaviour. They observed that when a material enters the superconducting state, it expels any magnetic field applied to it. Using meticulous measurements of the magnetic field inside and outside their samples, they showed that cooling a sample to its superconducting state caused the magnetic field inside it to vanish. Since the total magnetic flux—the number of magnetic field lines crossing a closed surface—must be conserved, the field outside the sample increased. In simpler terms, the magnetic field lines were effectively pushed out of the superconductor. This phenomenon, now called the Meissner effect, is what allows for technologies like magnetic levitating trains, where superconductors repel magnets to create frictionless motion.

With this experiment showing how superconductors are more than just ideal conductors, and indeed giving the community a clear definite property for these materials, the puzzle got bigger. How to explain this magnetic field repulsion?

Shortly after the discovery of the Meissner effect, the London brothers (Fritz and Heinz) suggested a phenomenological theory for superconductivity. This theory was based on observations of macroscopic phenomena and not on microscopic principles, hence the use of the word “phenomenological”. It accounted and explained the Meissner effect by introducing a special unit of length, the London penetration depth. This is the distance an applied magnetic field can penetrate into a superconductor before being expelled completely. This view is valid for small enough magnetic field, when the field reaches a critical value, the superconductivity breaks. This unit of length is often indicated as λ (lambda), and it is usually between 50 and 500 nm (nanometers) long. For comparison, a human hair is about 60,000-80,000 nm in diameter.

And so, by the mid-1930s, physicists had a phenomenological, macroscopic theory that described superconductors’ behavior but lacked a microscopic explanation of the underlying mechanisms. The answers began to emerge in the 1950s, a time of great scientific progress amidst a divided world. On one side, Ginzburg and Landau developed a theoretical framework grounded in phase transitions, applying it to superconductivity in a way that bridged the macroscopic and quantum realms. On the other, Bardeen, Cooper, and Schrieffer delved into the quantum mechanical underpinnings, constructing the groundbreaking BCS theory to reveal the microscopic origins of superconductivity. Stay tuned for the next post in this series, where we’ll explore how these theories reshaped our understanding of superconductivity.

Leave a reply to Superconductivity: The High-Tc Puzzle – The Spin of Things Cancel reply