In my previous post on superconductivity, I introduced the special phenomena related to this quantum state, zero electronic resistance and the Meisner effect, and the first phenomenological theory by the London brothers.

Clearly, such a macroscopic theory was not enough for physicists. They wanted to know more. They wanted to know what happens and the quantum level, and, possibly, why.

Answers to these questions came in the ’50s. At this point, the world is divided by the Iron Curtain and the two sides compete not only for political influence, but for scientific discoveries as well. The theory of superconductivity is a striking example of how science knows no border: the first crucial step came on one side of the Iron Curtain, when Vitaly Ginzburg and Lev Landau provided a framework to explain how superconductivity, a macroscopic phenomenon we can directly measure and see, arises from the collective behaviour of electrons. Some years later, on the other side, John Bardeen, Leon Cooper and John Robert Schrieffer put together all the puzzle pieces to give us a full quantum explanation.

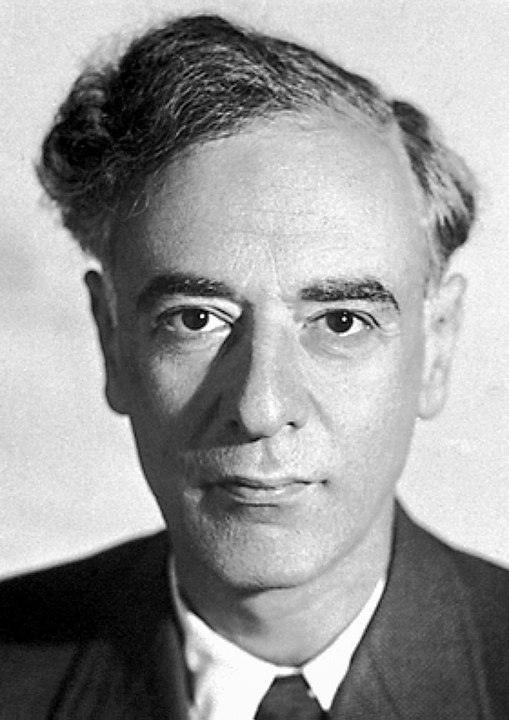

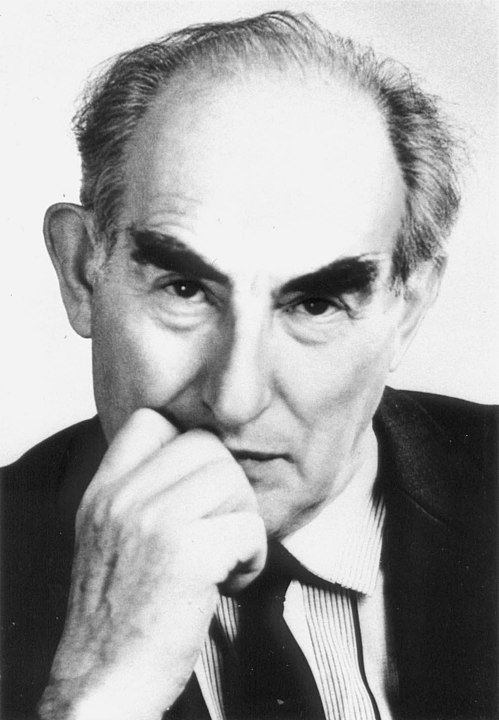

The first step towards a quantum theory of superconductivity came from the USSR, where Ginzburg and Landau managed to build a bridge between the micro and macro aspects of this phenomenon. While still giving us a phenomenological theory, based on observation rather than microscopic principles, they were the first to treat and show how superconductivity arises from the collective behaviour of electrons.

Lev Davidovich Landau is renowned for the Landau-Lifshitz Course of Theoretical Physics, a ten-volume series co-authored with Evgeny Lifshitz, which remains a key resource for physics students. He made groundbreaking contributions across many areas of theoretical physics and is considered one of the founders of modern condensed matter physics. In 1962, he was awarded the Nobel Prize in Physics for his work on superfluidity in helium-4. Unfortunately, he was unable to accept the prize in person due to severe injuries sustained in a car accident three years earlier.

Vitaly Lazarevich Ginzburg played a pivotal role in the development of the Ginzburg-Landau theory, extending Landau’s ideas on phase transitions to describe superconductivity. He also contributed to the Soviet atomic bomb project but chose not to continue when the project relocated and its secrecy intensified. In 2003, Ginzburg was awarded the Nobel Prize in Physics for his pioneering contributions to the understanding of superconductors and superfluids, an honor he shared with Alexei Abrikosov and Anthony Leggett.

Ginzburg and Landau’s theory builds on Landau’s earlier work on second-order phase transitions. A phase transition is a change in the state the material is in. A common one we experience almost daily in our kitchens is water freezing into ice, or ice cubes melting in our drink. This is an abrupt change, there is no in-between state between ice and water. We classify such transitions as first-order phase transitions. In most conventional superconductors, the transition is typically of the second order, with a smooth and continuous change.

For fluid water to turn into ice, its atoms need to restructure in space, forming a more ordered and fixed pattern. Similarly, for superconductivity to take place, electrons need to become collectively coherent in an ordered quantum state.

The formalism introduced by Landau was built on one key quantity: the order parameter. This quantity measures the relative amounts of ice and water in your cooling drink—or, in the case of superconductivity, how ‘superconductive’ a material is at each point in space. For second order phase transition, like in some superconducting materials, the order parameter changes smoothly with temperature. For first order phase transitions, instead, it jumps from zero to a finite value.

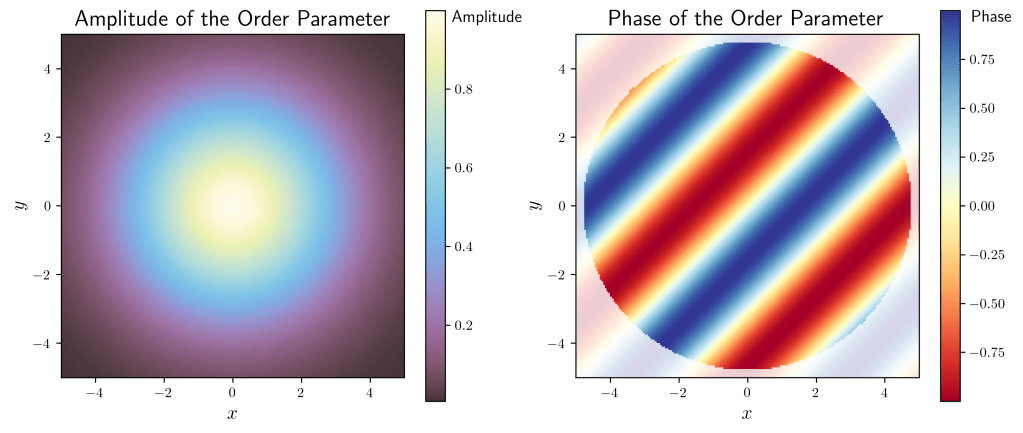

The order parameter of superconductivity is a bit special: instead of being just a number, it includes a phase as well. So one part will be an amplitude (how strong the superconductivity is) and the other accounts for how the superconducting wave is oriented. This double nature allows this quantity to predict how the superconductivity behaves inside the material, including how it disappears at the edges of it and how it weakens due to impurities and other external factors.

It can be hard to imagine a quantity with an amplitude and a phase as an order parameter. To help visualise the order parameter, let’s consider a common scenario: ripples on the surface of a bathtub. This quantity is perfect to describe waves, like the ones on top of a water surface. Let’s take bath time in my home. As the tub is filled with water and before I put my son in it, there are no ripples in it. As soon as my son starts throwing his toys in it, ripples appear on the surface. They will have a height (amplitude, or how intense the wave is), and a position on the water (phase, how the wave is oriented in space.

In the non-superconducting phase, the bathtub water is calm—no ripples. As the temperature cools and the superconducting state emerges, ripples appear on the water surface. These ripples have two features: their height (amplitude) shows how strong the superconductivity is, and their alignment (phase) shows how the waves are synchronized across the surface. Near the edges of the tub, the ripples weaken and eventually vanish, just like superconductivity fades at the material’s edges. If you disrupt the ripples by, say, setting your toddler into the tub, the coherent wave pattern breaks down—similar to how a strong magnetic field destroys superconductivity.

At the core of Ginzburg-Landau theory lies a fundamental concept in physics: systems naturally organize themselves to minimize their energy. This concept is formalized through a free energy functional, which is minimized to describe the superconducting state. This approach allows physicists to predict how superconductivity behaves in different conditions. With this assumption and a bit of advanced mathematics, Ginzburg and Landau were able to determine the equations describing the motion of superconducting electrons in materials.However, their theory relied on two phenomenological parameters, which could not initially be determined from first principles. These parameters—related to the coherence length and penetration depth—were later connected to microscopic properties of materials through the BCS theory.

The Ginzburg-Landau equations are still able to answer some important questions left open until now. The unexpected phenomena discovered together with superconductivity are captured by this theory: a frictionless current, also called supercurrent, arises naturally from the equations. The Meissner effect, where the magnetic field is expelled by the superconductor, and the penetration depth (previously described by London theory) are both captured within the Ginzburg-Landau framework. By minimizing the free energy functional, the GL theory provides a unified description of these key properties of superconductors, rooted in the macroscopic behavior of the order parameter.

It’s the beginning of the ’50s, the midpoint of the century, and we have a first idea of how superconductivity works. thanks to the groundbreaking work of Ginzburg and Landau. By the end of the decade, we will also know why. Building on the foundation laid by Ginzburg and Landau, John Bardeen, Leon Cooper, and Robert Schrieffer developed a full quantum theory of superconductivity in 1957. Known as the BCS theory, it explains the underlying mechanism that gives rise to this extraordinary state of matter. See you on the next part of this series in superconductivity, as we take a dive into a quantum fluid of electrons to understand BCS theory.

Leave a reply to Superconductivity: Origins – The Spin of Things Cancel reply