It is now the second half of the ’50s. Elvis Presley plays on radios and in cinemas, the Warsaw Pact has just been signed, and the Vietnam war has just started. Amidst these global events, physicists are still trying to crack the fundamental puzzle of superconductivity: what microscopic mechanism leads to this phenomenon?

At this point, there is a framework coming from the USSR: the Ginzburg-Landau theory. While accounting for all of the characterising phenomena of superconductivity, this theory is not yet able to give an answer to the big how and why questions. What it does is describing the phase transition from the normal to the superconducting state and introducing a special order parameter to describe this. You can find more in my previous post.

But on the other side of the trenches, a physics trio is preparing to unveil a revolutionary theory: the BCS theory, from the names of its inventors, John Bardeen, Leon Cooper, and John Robert Schrieffer.

John Bardeen remains the only person to have received the Nobel Prize in Physics twice, first in 1956 for the invention of the transistor, alongside William Shockley and Walter Brattain, and then in 1972 for the BCS theory. He contributed the pivotal idea of the superconducting state requiring an energy gap.

By Nobel foundation – http://nobelprize.org/nobel_prizes/physics/laureates/1956/bardeen-bio.html, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=6155225

Leon Cooper is best known for his role in developing the concept of Cooper pairs—quasiparticles formed by two electrons bound together, a cornerstone of the BCS theory of superconductivity. Later in his career, he turned his attention to neuroscience, contributing to the understanding of synaptic plasticity through the BCM theory (Bienenstock, Cooper, and Munro model).

By Associated Press – [1] [2], Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=153208915

John Robert Schrieffer had an epiphany while riding the New York subway: the superconducting ground state should be described by a single collective wave function encompassing all Cooper pairs, rather than treating each pair individually. This breakthrough was key to the development of the BCS theory. Schrieffer also dreamed of uncovering the secret to room-temperature superconductivity.

By Unknown author – [1] Dutch National Archives, The Hague, Fotocollectie Algemeen Nederlands Persbureau (ANEFO), 1945-1989, CC BY-SA 3.0 nl, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=20427867

The BCS theory solves the superconductivity puzzle at a microscopic level and connects the macroscopic phenomena to microscopic quantum principles. It is one of the first theories to show the concept of emergent phenomenon, when macroscopic observations derive from collective behaviour of particles, rather than from accounting for each single one.

At the heart of the theory lies the fundamental particle pushing the main characteristics of most known solids and crystals: the electron. Better yet, the collective behaviour of electrons.

Electrons are fermions and as such obey the Pauli principle: two electrons cannot be in the same state at the same time. A quantum state is defined by a set of quantum numbers. For electrons in a solid, a good set is energy, position, and spin. All electron have to have different values of this set at a given moment. Moreover, electrons are charged particles and they all carry the same, negative, charge. Charges with the same sign repel each other, adding one more reason for electrons to be loners. They just want to be left alone and not even go to prom. But electrons in solids aren’t just floating in empty space – they’re moving through a precise arrangement of atoms: the crystal lattice.

This orderly grid of atoms adds a crucial new element to our story, as it can deform and vibrate in response to the electrons moving through it and to other factors, such as temperature. The vibrations in a lattice are effectively described by special quasiparticles: phonons. A quasiparticle behaves like a particle, following the same quantum equations and principles, but only exists as a collective excitation and cannot be found out of the many-body system.

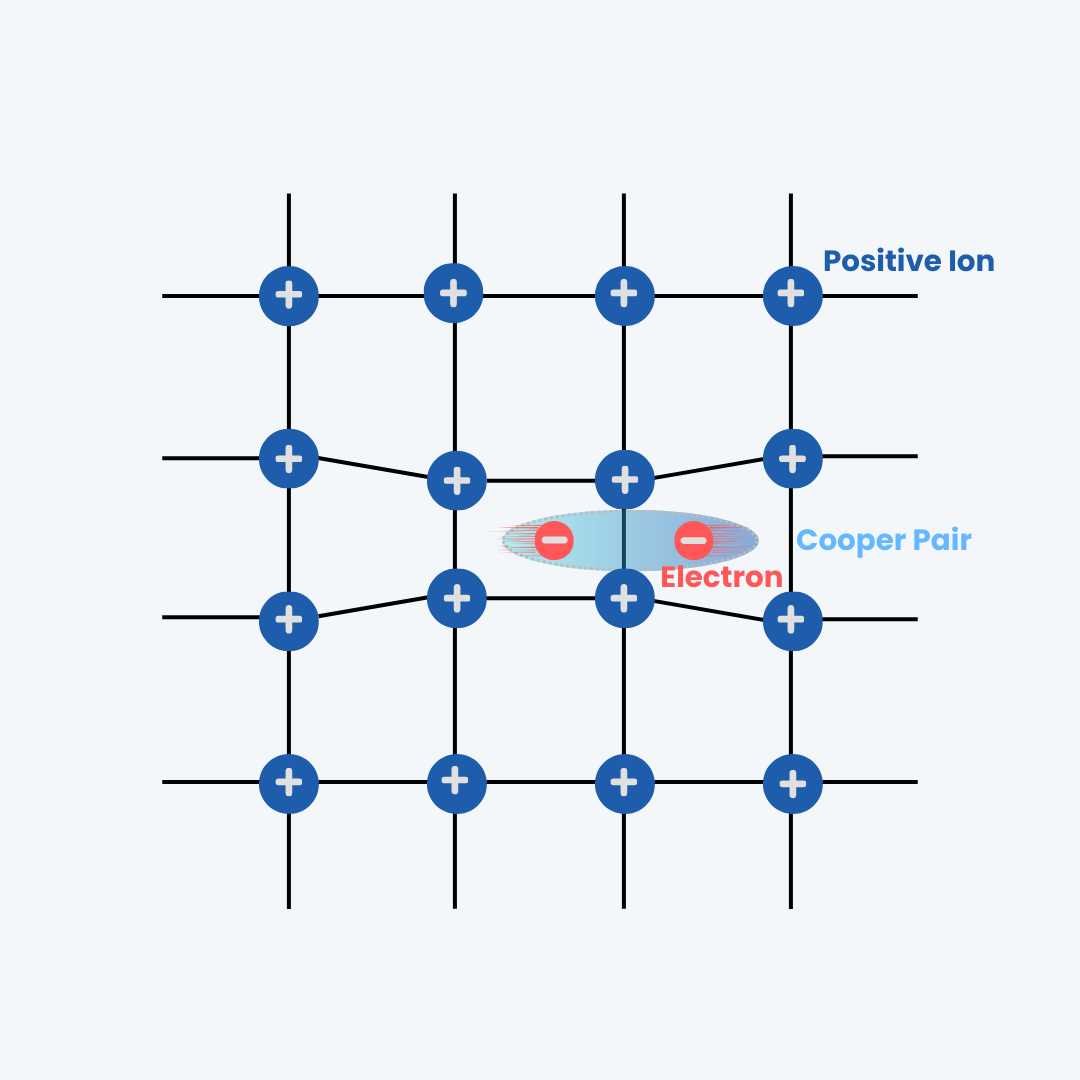

These lattice vibrations, or phonons, act like messages passing through the crystal. While lone electrons naturally repel each other, these vibrational messages can actually cause something remarkable: they can make two electrons attract each other. So, while the lone electrons do not want to attend the ball, phonons are their pushy friends convincing them to just get close enough to that other cute electron over there. And just like that, two electrons form a dancing pair, held together by an effective attractive force mediated by the friendly phonons. These special electron pairs are called Cooper pairs.

As the Cooper pairs start dancing and flowing together, like synchronised dancers. This strong synchronisation leads to a quantum coherent state only allowed by the collective dance. Looking at a single Cooper pair would not be enough to understand superconductivity, zooming out to the whole dance hall and the many-body behaviour shows us the beauty of this collective state.

The formation of a Cooper pair: Lattice deformation, caused by the presence of an electron, creates a phonon that mediates the attractive interaction between two electrons, allowing them to form a Cooper pair.

Visualizing the Bose-Einstein condensate of Cooper pairs: a coherent quantum state where electrons pair up and move in perfect harmony, giving rise to the remarkable phenomenon of superconductivity.

The formation of Cooper pairs and the subsequent coherent quantum state is due to a fundamental change in how the electron pairs behave when compared to single electrons. While a single electron is a loner, pairs are now social animals. The binding of two electrons results in the pair being now a boson rather than a fermion. Bosons do not obey the Pauli principle. On the contrary, they can form what is known as a Bose-Einstein condensate, with all bosons in the same quantum state. This condensate is the coherent quantum state needed to explain and understand superconductivity. In short, the full set of Cooper pairs is described by one single macroscopic wave function with a coherent phase across the whole superconductor. Now the dance hall is full of synchronised dancing pairs moving in unison, so that if we look from above we will see a single coherent movement and flow across the dance floor.

Besides the beautiful idea of many Cooper pairs behaving as one big coherent state, the condensate has important physical applications. First, it explains the formation and flow of a supercurrent. Single electron in metals behave like cars trying to go home during peak hours: they have to deal with congested traffic. On the other hand, Cooper pairs move seamlessly in special carpool lanes, no traffic involved. Hence, the charge moves in the superconductor without meeting any resistance.

But the story of our synchronized Cooper pairs explains more than just frictionless current flow. Their collective behavior also reveals why superconductors and magnetic fields have such a peculiar relationship. The Meissner effect – the expulsion of magnetic fields – emerges from the special boson condensate of Cooper pairs. When a magnetic field is applied to a superconductor, it only penetrates for a short depth. The superconductor has a way of preserving its “field free” state by shielding itself through the creation of surface currents. As moving charges create a magnetic field, the surface current is build to create a magnetic field opposite to that applied to the superconductor. These currents emerge as the superconductor strives to minimise its free energy, wanting to stay in the minimal energy state. Kind of similar to when your toddler runs into your bed on a Sunday morning and you ask your partner to take over for a couple hours, so that you can minimise your energy by staying in bed a bit longer.

Such an idyllic visual seems ready to be shuttered at any time by external factors, like someone abruptly turning off the music. However, this is not that easy. In fact, the superconducting state is protected and characterised by an energy gap. Think of it as an energy barrier any external factor has to pass in order to affect the state. in our dance hall analogy, the dancers are protected by an energy bubble that cannot be easily disturbed by external factors, so that turning off the music requires enough strength to get through the bubble first. The superconducting flow is hence protected by common alterations, such as lattice vibration and impurities.

With the Cooper pairs, the collective wave function, and the energy gap, the BCS theory gives us the needed quantum framework and understanding of superconductivity. Previous equations, including the London penetration depth and the Ginzburg-Landau coherence length, can be derived within this theory. Lev Gork’ov derived a version of the Ginzburg-Landau theory starting from the BCS formalism, proving how insightful the phenomenological theory really was.

The BCS theory finally bridges micro to macro, giving us the quantum answers with a series of wonderful ingredients and proving how emergent phenomena and collective behaviours are key in understanding condensed matter and general many-body systems.

It all seems complete at this point: from Kamerlingh Onnes’ discovery of zero resistance in cooled mercury wires to the quantum framework of superconductivity provided by BCS theory, it feels like the puzzle has been solved. Yet, 30 years later, Georg Bednorz and Karl Alexander Müller would uncover a new class of superconductors with much higher critical temperatures—opening an entirely new chapter and giving physicists a new puzzle to solve.

Leave a reply to Superconductivity: Decoding the Transition – The Spin of Things Cancel reply