In the last month, we have seen how Kamerlingh Onnes discovered a new phase of matter thanks to his state-of-the-art low-temperature laboratory: superconductivity. We went past the drop in resistance and found how the defining property of superconductors is the Meissner effect: a superconductor expels magnetic field. We have worked our way to solve the puzzle of how metals turn into superconductors at low temperatures, and why, exploring the Ginzburg-Landau theory, introducing the right order parameter for this phase, and finally found the quantum answer to unlock the puzzle, the BCS theory. It is the end of the ’50s, all is well.

And all was well on the superconductivity front for 30 years. Physicists were confident in their understanding of superconductivity and were tirelessly working on finding or synthesising a material that would exhibit superconductivity at room temperature.

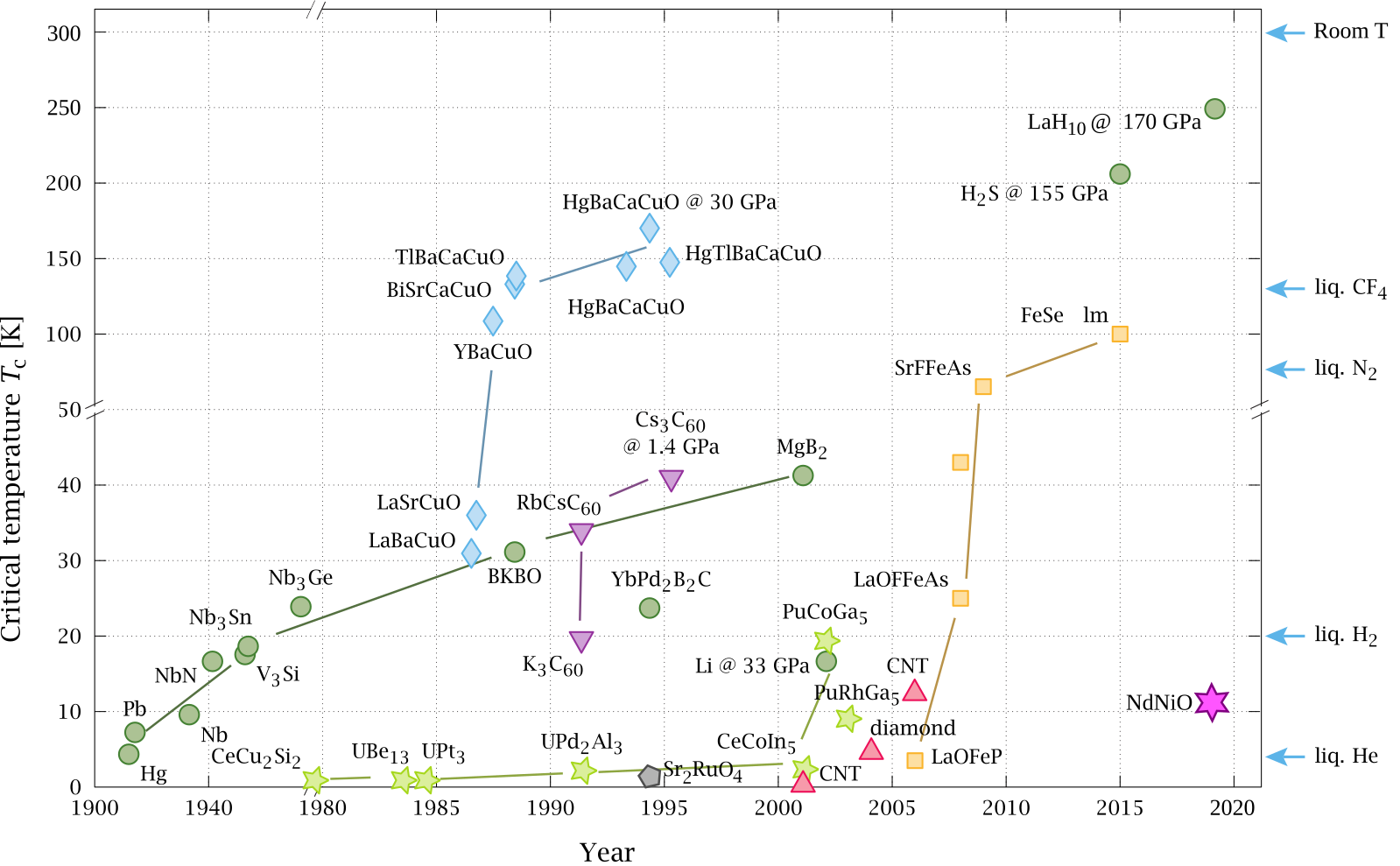

However, while in the first decade they had managed to increase the transition temperature (the temperature at which the phase transition from normal to superconducting state occurs) up to around 23K (-250.15˚C), they then hit a plateau that wen on for about 15 years. Until, in 1986, IBM researchers Georg Bednorz and K. Alex Müller uncovered the box of cuprates, or copper oxides.

Georg Bednorz (b. 1950, Germany) was born to Silesian refugees and initially studied chemistry before shifting to crystallography. A summer internship at IBM Zürich introduced him to K. A. Müller, leading to a PhD at ETH Zürich and later a research position at IBM. His collaboration with Müller on copper oxides led to the groundbreaking discovery of high-temperature superconductivity in 1986, earning them the 1987 Nobel Prize in Physics. [Krzysztof Popławski, CC BY-SA 4.0 , via Wikimedia Commons]

Karl Alexander Müller (1927–2023, Switzerland) studied physics at ETH Zürich, where he attended lectures by Wolfgang Pauli and where he later earned his PhD. After working at the Battelle Memorial Institute, he joined IBM Zürich Research Labs, focusing on complex oxides. His collaboration with Georg Bednorz led to the discovery of high-temperature superconductivity in 1986, earning them the 1987 Nobel Prize in Physics. Having lived in Lugano as a kid, in the Italian-speaking Swiss region, he could speak fluent Italian. [Ibmzrl, CC BY 3.0 , via Wikimedia Commons]

Cuprates are ceramic materials composed of copper and oxygen atoms, combined with other elements like rare earths or transition metals.

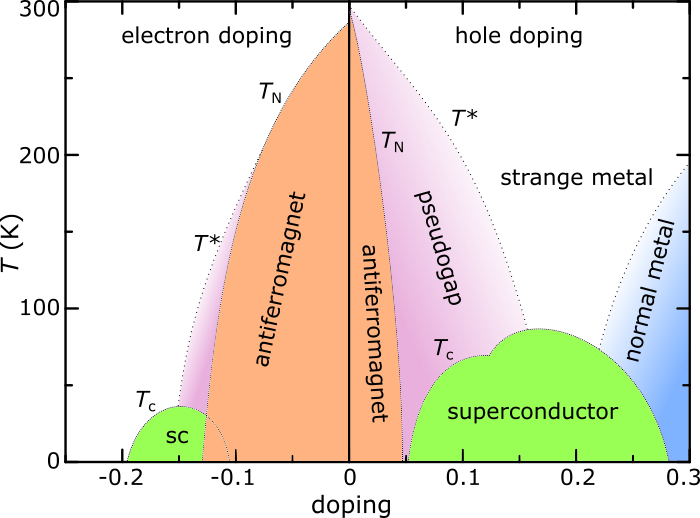

The first material measured by Bednorz and Müller was La2−xBaxCuO4. Here, x is a so-called doping parameter that can be varied. The variation of this parameter changes the amount of active charge carriers (electron or holes, which are the lack of an electron in solid state systems, once again, a quasiparticle). By changing this number, researchers are able to span the phase diagram of cuprates, which is much richer than previously considered superconductors. More on this below.

The temperature reported by Bednorz and Müller for this first observation was 35K (-238.15˚C). The discovery was soon confirmed by other research groups, together with a plethora of measurements on other materials in the same cuprates class, showing even higher transition temperatures. These temperatures, while still far from room temperature, were high enough to allow superconductivity with liquid nitrogen instead of costly liquid helium—an enormous technological advantage.

Overview of different superconductors discovered from 1911 to 2015. Different colours and symbols refer to different class of materials. Cuprates are light blue rhombohedra, Iron Pnictides are yellow squares. In some cases, pressure is specified.[PJRay, CC BY-SA 4.0 , via Wikimedia Commons]

A schematic of the doping phase diagram of cuprate superconductors. Above the superconducting dome, a pseudogap phase emerges, where an energy gap appears only for electrons moving in specific directions in momentum space. One could imagine moving freely along a street (no gap) but encountering walls that block motion across it (energy gap), reflecting the directional nature of the pseudogap. [Holger Motzkau, CC BY-SA 3.0 , via Wikimedia Commons]

This breakthrough didn’t just push the transition temperature higher—it made superconductivity dramatically more accessible. Liquid helium, though crucial for early superconductors, is rare and expensive. With cuprates, liquid nitrogen (which is far cheaper and more abundant) was enough to sustain superconducting states, paving the way for real-world applications like MRI machines, maglev trains, and more efficient power grids.

So far so good, finally a jump in the temperature range has been achieved. But, there’s a catch. The beautiful and encompassing BCS theory fails to explain the microscopical mechanism behind this High-Tc superconductivity.

BCS theory assumes a force mediated by electron-phonon interactions. However, this is clearly not the driving force behind superconductivity in cuprates. Cuprates are strongly correlated materials, meaning it is impossible to treat electrons as freely moving, rather their interactions are so strong that the movement of one of them causes a cascading effect throughout the system.

Going back to the dancing Cooper pairs mentioned when describing the BCS theory, we can now think of an opposite scenario. Instead of coordinated couples in a dancing hall, electrons are more like people in a mosh pit at a metal concert. While there is some form of coordination amongst participants to avoid injuries, a mosh pit does not follow that ordered flow seen at a ball. Nonetheless, emerging patterns still appear from the apparent chaotic motion of mosh pits, and the complex collective behaviour of cuprates follows a similar pattern, with the caveat that these strong correlations make describing the system much harder than modelling a simple metal.

Many theories have been put forward to describe cuprates and other unconventional superconductors, like iron pnictides. Still, none of them has been widely accepted. Part of it is because there are many different contributors to the physics of these unconventional superconductors. It is clear that their peculiar electronic structure and underlying symmetry play a role. But so do quantum fluctuations and magnetic interactions between spins.

The latter is considered by many to be a crucial player in this unconventional field, as superconducting cuprates are derived by doping antiferromagnetic Mott insulators. An antiferromagnet is a system characterised by long-range magnetic order. In opposition to a ferromagnet, where spins, the quantum bricks of magnetism, order pointing all in the same direction, in antiferromagnets spins order alternating opposite directions. Undoped cuprates fall in this category, and it is unclear how the magnetic order melts into the superconducting state and how the magnetic correlation keep surviving even well into the latter. And that’s not all there is to the phase diagram: other, competing, states emerge as well, including the always puzzling pseudo-gap phase and a charge-density wave state.

With all these competitors and key players, the driving force leading to the superconducting state remains a mystery, with new clues awaiting to be discovered.

These materials remain a battleground for competing theories, with new insights, rebuttals, and heated debates shaping our understanding each year. I even had the opportunity to contribute to this field with one of my favorite research papers, adding a small piece to the puzzle.

Unlocking the physics behind cuprates and other unconventional superconductors could allow us to engineer new materials, pursuing the goal of a room temperature superconductor. The latter could revolutionise the way we move in and between cities and the energy distribution and storage. A (almost) fully no-dispersive power grid would transport energy with minimal loss on the way, reducing the energy production needs and bringing us closer to a greener future.

Leave a comment