Everybody has some idea of what a magnet is. Maybe it’s a red and blue bar, or a memento from a trip that is now sticking on your fridge. But how do magnets actually work?

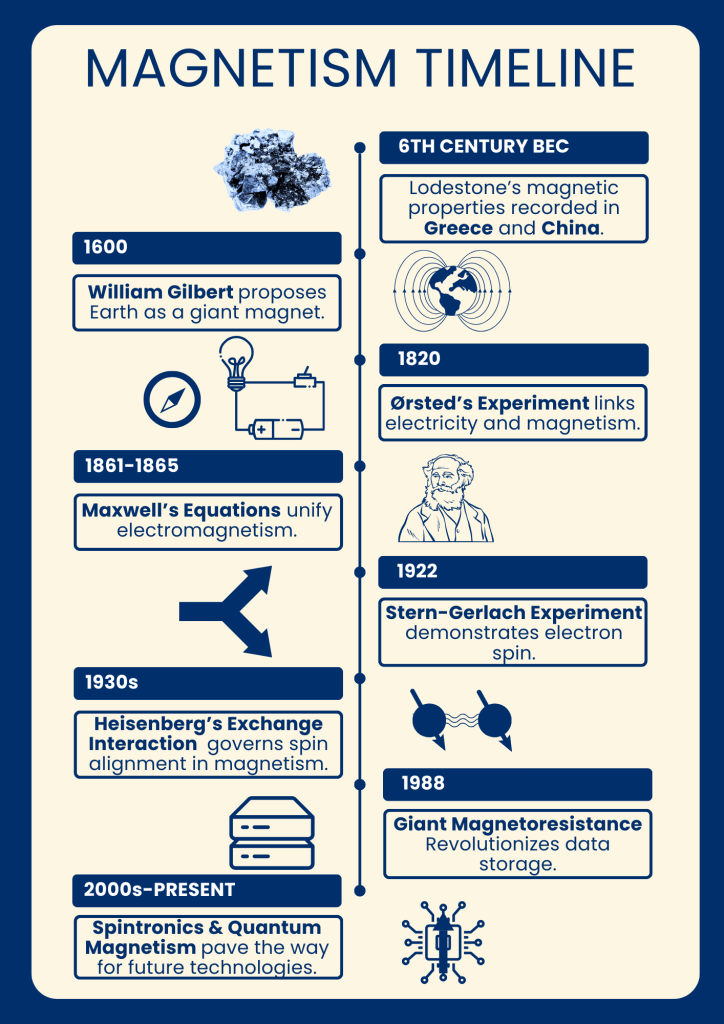

Magnetism was already known in ancient Greece, as Greeks observed the magnetic behaviour of lodestone. In fact, the word magnetism comes from the Greek μαγνῆτις λίθος (magnētis lithos, the Magnesian stone, lodestone). In Asia, magnetism is reported both in India (a medical treaty reporting the use of lodestone to remove arrow heads) and in China. Here, we also have the first observation and usage of magnetic compasses. It took several centuries before we knew magnetic compasses work thanks to the Earth’s magnetism rather than a force coming from the stars.

Then came the 19th Century. This was a fruitful time for magnetism, or, to be more precise, electromagnetism. A number of big scientists contributed ideas and observations, culminating in Maxwell’s equation, a beautiful set of equations describing classical electromagnetic forces, and how magnetism arises from moving electrical charges.

Still, a big problem was left open: how do magnets actually work? Why is a material, like lodestone, able to exert a magnetic force, while others, like a piece of marble, aren’t? In other words, why do some materials have a built-in magnetism, even when no current flows?

We had to wait for the 20th century, and the quantum mechanics revolution, in order to get an understanding of magnetism in materials.

At the heart of quantum magnetism is a fundamental property called spin. An electron has a series of properties: its position (or momentum), its energy, and its spin. The spin is a purely quantum property that behaves similarly to angular momentum. In classical mechanics, angular momentum measures how much an object resists changes to its spinning motion. The more angular momentum an object has, the harder it is to stop it from rotating. Spin behaves similarly in that it represents an intrinsic resistance to changes in orientation, but unlike angular momentum, it doesn’t involve any physical rotation.

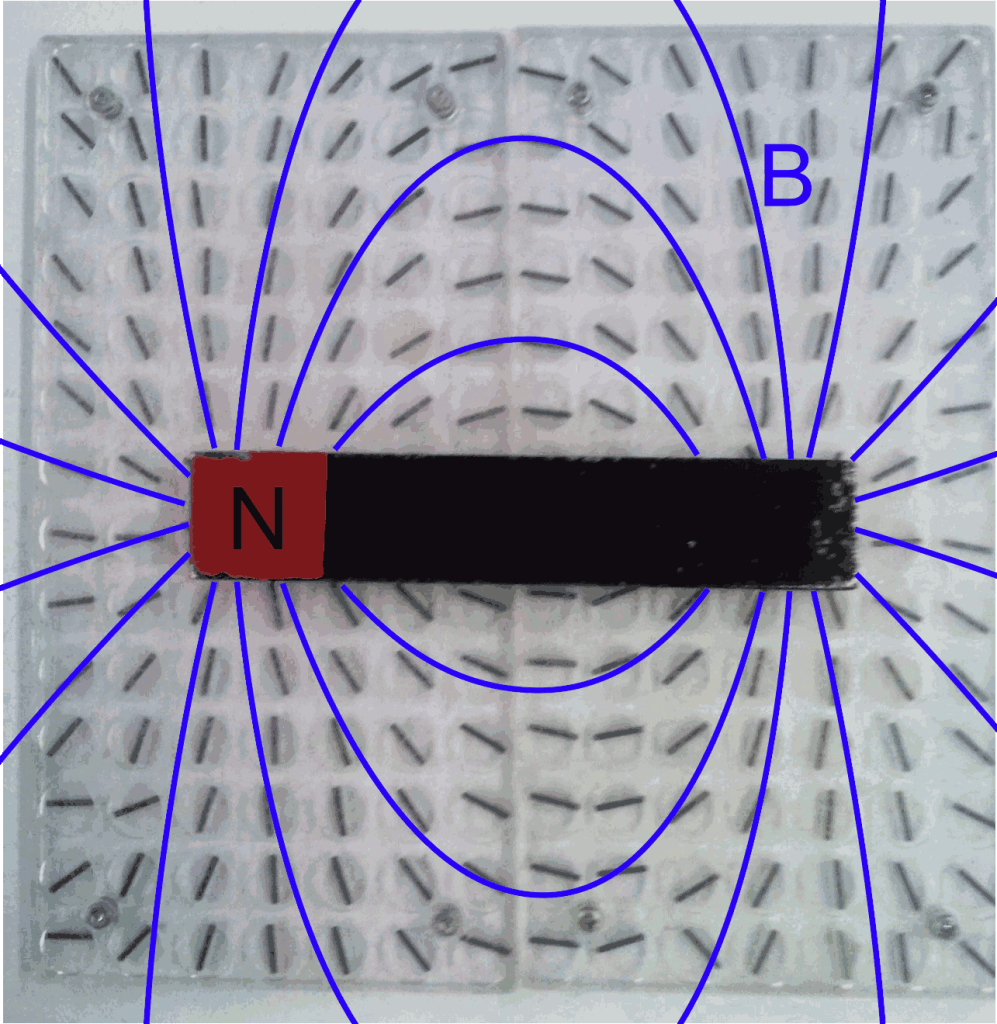

Electronic spins generate tiny magnetic moments, making them behave somewhat like bar magnets, but their quantum nature makes their interactions much richer than classical dipoles. Being a quantum property, electronic spins are quantised, taking only the projection values +1/2 and -1/2, the smaller possible value for a quantum spin.

The above keeps being true also for electrons in an atom, but now they also carry another quantity: the orbital angular momentum. This quantity sums up with the electron spin following some special quantum rules (yes, even sums are different when quantum mechanics is involved), and contribute to the magnetic properties of the atom.

In solid state systems, a hard-to-imagine number of atoms order on a fixed grid, referred to as a lattice. This geometrical order creates an electrical field, also referred to as a crystal field, due to the charges and magnetic properties of the single atoms interacting with each other. This crystal field can, at times, suppress the orbital contributions to the magnetic properties of the valence electrons (the electrons on the outer atomic orbitals, which are responsible for the material properties).

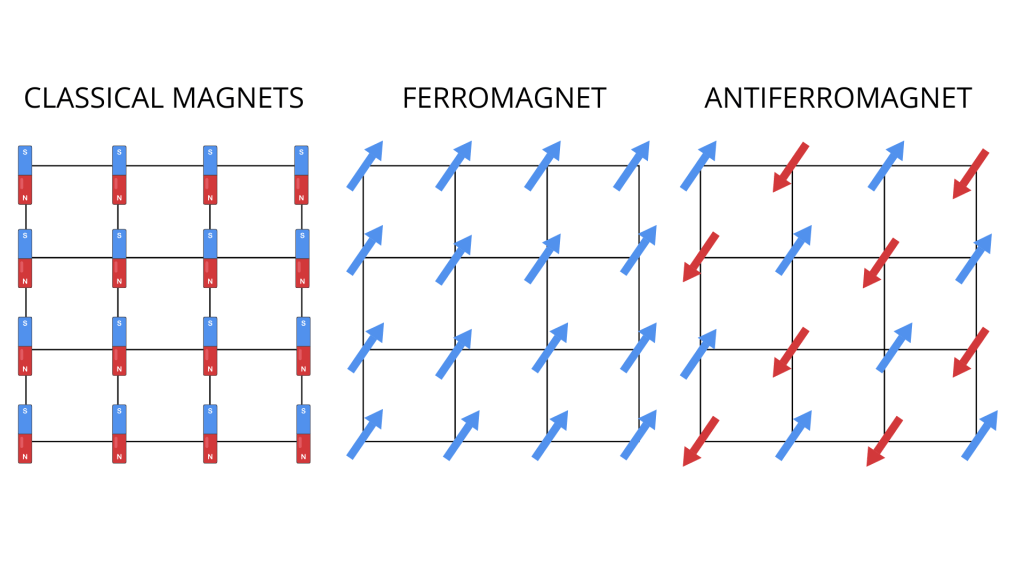

The interplay of electron spin, angular momentum, and crystal field determine the magnetic properties of a material. For example, if all the atomic magnetic moments point in one direction, the material will exhibit a macroscopic magnetic field and will behave as a magnet and stick to your fridge. On the other hand, if each moment is free to point anywhere independent of the others, the material will be a paramagnet with no net macroscopic field. So what decides whether a material becomes a permanent magnet?

Classically, we would expect spins would tend to align and point at the same direction, similar to what magnetic bars would do when put next to each other. But once more, quantum properties make things different at the micro scale. Reducing the electron to tiny magnetic dipoles is a misleading approximation. We have to remember: these are quantum particles. As such, they are indistinguishable. Moreover, they are fermions obeying the Pauli exclusion principle, stating that two fermions cannot occupy the same quantum state. Their spin orientation is part of the properties defining this state.

Because electrons are indistinguishable quantum particles and obey the Pauli exclusion principle, their wavefunction must follow specific symmetry rules. These rules, in turn, influence how electrons interact, leading to an energy difference depending on whether their spins are aligned or anti-aligned. This energy difference is what we call the exchange interaction.

In real materials, electrons can be close together, so that their wavefunctions overlap. Changing their spin orientation affects the energy of the whole system. In some cases, spins aligned in the same direction will be energetically favourable (ferromagnetism), in others, anti-alignment might be the preferred solution (antiferromagnetism). The chosen alignment will be the one lowering the total energy, as a system tends to be in a state with the lowest energy possible. The way spins align in a material define its macroscopic magnetic properties.

But whether spins tend to align or anti-align is not enough to tell us what the magnetic properties of a system are. The underlying geometry on which the atoms sit plays an important role. The dimensionality of the system (whether it is just a chain of atoms or a full three-dimensional lattice) constrains the physical properties we find, but can also give rise to exotic phenomena.

The world of quantum magnetism goes beyond permanent magnets and spins pointing in the same or in alternating direction. A number of beautiful patterns can arise depending on the interplay of all the ingredients we have seen here. In the next posts, I’ll try to bring you along for an exploration of magnetic orders, weird excitations, open problems, and future applications.

Leave a comment