A lot has been said about Mildred Dresselhaus, the Queen of Carbon. She was a star in physics and beyond, going as far as becoming a pop culture reference, at least in the US, where a famous General Electric commercial featured her as the protagonist while asking the question “What if female scientists were celebrities?”

From Music to Physics: A Path Forged in Determination

Prof. Dresselhaus came from the Bronx, attended a music school on a scholarship, but realised her passion was in science relatively soon. She was supported, if not nudged, by her lecturer Rosalyn Yalow to pursue a PhD in Physics. And so she did, encountering barriers due to her gender on the way, like not being able to take exams in the same room as her male classmates at Harvard. After getting her master degree at Radcliffe College (while attending classes in Cambridge), she moved to the University of Chicago for her PhD. There, she spent a year working and studying under Enrico Fermi, before his death in 1954.

Her PhD work was on the microwave properties of superconductors in magnetic fields. She had to build her own material from equipment kept in storage under the football stands. But she did it, building superconducting wires, microwave equipment, and producing liquid Helium as well.

When joining the Lincoln Lab at MIT in 1960, she moved away from superconductors to a different class of materials: semimetals. These are a class of materials falling in between metals and non-metals. They have a very special band structure. In solids, the electronic band structure determines their thermoelectrical properties.

How Band Structure Defines a Material

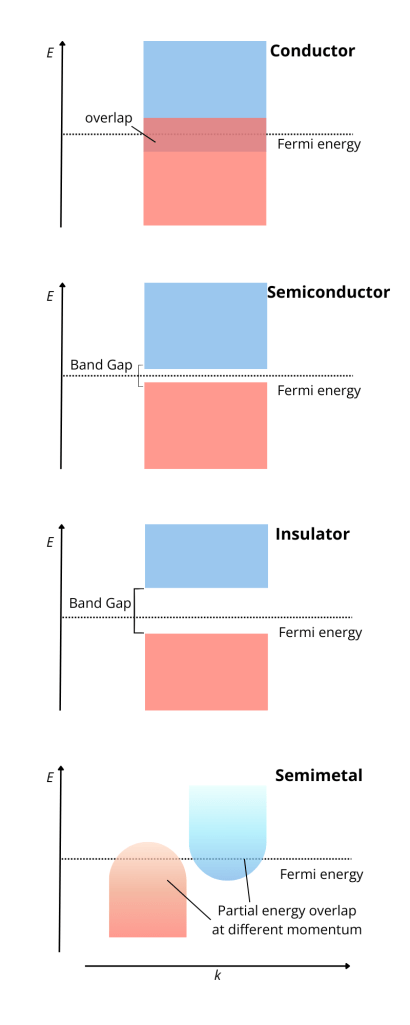

To determine in which class a materials falls into, one has to look at the relative positioning in terms of energy of the conduction and the valence band. The valence band is the ground-state (or lowest energy) band that can be occupied by electrons. This is determined by the atomic properties of the material in question. Being lower in energy, electrons in the valence band are more tightly bound to the atomic nuclei and hence less free to move. They do not contribute to carrying charge or heat around the material.

On the other hand, electrons in the conduction band have higher energy and are free to move and determine the transport properties of a system. At room temperature, this band is empty or partially filled, while the valence band is full or partially filled.

The distance in energy between these two bands, referred to as the energy gap, determines the conducting class of the material. If the bands overlap (no energy gap) and electrons can easily pass from one band to the other, we have a conductor. If the gap is small, so that exciting an electron from the valence band to the conduction band is relatively easy, we have a semiconductor. Finally, if the energy gap is large, we have an insulator.

To draw a better picture, we can think of the valence band as a very full parking lot, where cars (electrons) are stuck and cannot move around freely. On the other hand, the conduction band is more like a highway, with smooth traffic, allowing cars (electrons and electricity) to flow. In metals, the parking lot and the highway overlap, allowing for easy electrify, or traffic, flow. In semiconductors, there’s a small barrier between the parking lot and the highway, so only some cars can jump over (with enough energy). In insulator, the barrier is too high, so there is no access from the parking lot to the highway and no flow.

The Unique Properties of Semimetals

Semimetals, like carbon and bismuth, have small energy overlap between the bottom of the conduction band and the top of the valence band. Unlike metals, where the conduction and valence bands overlap at the same momentum, in semimetals they touch at different points in the Brillouin zone, affecting their charge transport properties. They have lower electrical and thermal conductivities compared to metals, but higher than insulators or semiconductors. In semimetals, electrical charge is carried by both electrons, like in metals, and holes, which behave like positively charged particles.

Holes play a key role in many condensed matter phenomena and materials, from semimetals to unconventional superconductors and exotic magnetic behaviour. Understanding where electrons and holes are places in a band structure, meaning assigning bands correctly to the different charge carriers in a material, is fundamental to make the correct prediction about its physical properties.

Correcting the Band Structure of Graphite

Dresselhaus and her team discovered that there had been an error in the previously assigned electron and hole bands in the band structure of graphite. This material is what makes up pencil tips and it is a form of carbon made up of different layers, or sheets, each of which has a hexagonally arranged carbon atoms (honeycomb lattice).

Dresselhaus and her group went on to study graphite and related materials for decades. She was among the first to predict and characterise the properties of carbon nanotubes, paving the way for their modern applications. She studied intercalated materials, sandwiching different compounds between graphite layers, including studies on superlattices that led to the development of lithium-based batteries. To dig deeper into carbon nanostructure, she adapted resonance Raman spectroscopy to fit her goal.

Raman Spectroscopy: A Window into Carbon Nanostructures

Raman spectroscopy makes use of the Raman effect. Discovered by Indian physicist C. V. Raman, it describes how photons interacting with a material can be scattered at different wavelengths due to energy exchanges with molecular vibrations. Shining light on materials can hence give us information about its vibrational and structural properties.

Since we are talking about scattering, it is easy to imagine scattering billiard balls on a table. Let’s pretend to push a ball agains a stationary ball. If it bounces off unchanged, this is the normal light scattering (also known as Raleygh scattering). On the other hand, if it transfers some energy to the stationary ball, then it’s energy coming back has changed, similar to what happens in the Raman scattering process between photons and molecules.

Mildred Dresselhaus worked with Raman spectroscopy to characterise single-wall nanotubes and other carbon-based nanostructures. In particular, she made use of the diameter-selective Raman effect, which allows for the characterisation of nanotubes based on their diameter using Raman spectroscopy. This mainly follows from two contributions: the resonant nature of the Raman scattering in nanotubes, meaning the intensity of the Raman signal is greatly enhanced when matching the transition energies of electrons in the nanotube, and the strong diameter dependence of certain resonances.

The Lasting Impact of Mildred Dresselhaus: A Legacy Beyond Science

Her contributions to nanoscience are immense, but this is not the only legacy she left behind. Mildred Dresselhaus was the first woman to be full professor in physics at MIT. She was always available to mentor female students and early researchers, even besides her own research group. Together with 16 colleagues, she called out current discriminations at MIT, sparking a campaign for change. In her honour, the American Physical Society has instituted the Mildred Dresselhaus Fund in order to support young women in physics.

Dresselhaus’s commitment to advancing women in STEM was integral to her career and legacy, making her not only a scientific trailblazer but also a crucial figure in the fight for gender equity in science and engineering. In these times of pushback against all that has been accomplished by inclusive policies in STEM disciplines and beyond, it is important to remember those that came before us and spoke about discrimination when nobody was doing so. Additionally, while science funding is being cut in the USA, let us remember that Dresselhaus’s career was supported also through an NSF grant when she was a postdoc.

How many future Mildred Dresselhauses might be lost due to current policies undermining science and education? It is hard to know, but it is worth asking.

Leave a comment