Nuclear physics is deeply rooted in quantum mechanics, and few have contributed as much to its foundation as Fay Ajzenberg-Selove.

From Berlin to New York: A Life Marked by Resilience

Born in Berlin in 1926, her early life was characterised by moving around, first to Paris, due to economic circumstances (Great Depression), and later, before the Nazi invasion of France, to New York City, through a perilous journey touching Spain, Portugal, the Dominican Republic, and Cuba. Once in NYC, the Ajzenberg family finally settled permanently.

Ajzenberg-Selove attended the all girl Julia Richmond school, with her father insisting that she learns typing to be able to make a living in case she would not admitted to university. However, she always wanted to be an engineer, just like him, and he had always shown support in her scientific inclinations.

Breaking Barriers in Education

She never had to rely on typing though, as she was accepted at the University of Michigan, at Purdue, and had had an interview at MIT. Here, she had learned she would have to pass through two different filters to get in, as the institute had a numerus clausus for both women and Jews, both categories under which she fell. She went on graduating with a BS in engineering in Michigan, the only woman in a class of 100 students.

While engineering suited her talent, she found physics more stimulating and decided to continue her studies in her field. First, she attended a year at Columbia University, to then enrol for graduate studies at the University of Wisconsin-Madison. It is here that the research work that would define her scientific legacy began.

A Pioneering Career in Nuclear Physics

With her doctoral work titled Energy levels of some light nuclei and their classification, she entered the field of nuclear level characterisation. A field she never left and defined with her life work, the series Energy Levels of Light Nuclei.

Her influential work focused on understanding the structure of atomic nuclei. To appreciate its significance, let’s take a step back and explore what happens inside a nucleus.

Most people with a high school education will remember that atoms are made of electrons, protons, and neutrons, and that the last two entities are also referred to as nucleons and are at the center of the atom in what is referred to as the nucleus.

Understanding Nuclei: The Physics Behind Her Work

Proton and neutrons in nuclei are confined in a small space. This confinement, together with nuclear forces and quantum effects, leads to the emergence of quantised energy states, meaning nucleons can only have certain energy values. Those values are influenced by the strong nuclear force acting on all nucleons, and the electromagnetic repulsion between positively charged protons. The interplay of these interactions is described by the shell model, which describes how nucleons fill these energy levels.

Similar to how electrons are assigned quantum numbers in the atomic model, nucleons have different quantum numbers depending on the shell they occupy, their parity, angular momentum, and isospin.

As proton and neutrons have almost exactly the same mass, they can be interpreted as two different sates of the same particle. To characterise these states, a new quantum number is needed: the isospin. Although named in analogy to spin, isospin does not represent a real angular momentum. And while the idea that neutrons and protons are different states of the same particle led to the introduction of isospin as a quantum number, it was only later, once quarks were discovered, that physicists realised the isospin carries information on the quantity of up and down quarks in a nucleon, with the proton having two up and one down quark, while the neutron has two downs and one up.

Mapping Energy Levels: The Significance of Her Work

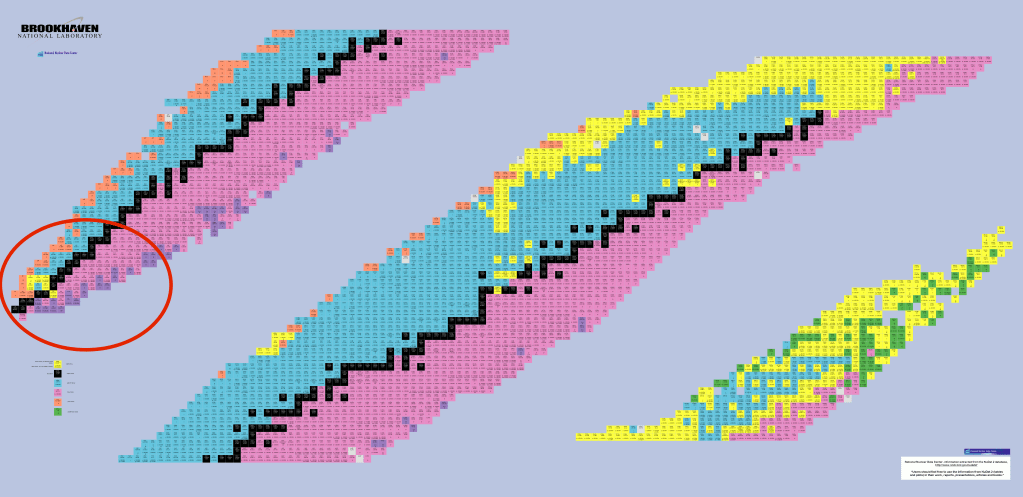

During her work, Ajzenberg-Selove focused on the excitation of nucleons to higher energy levels and the way the subsequent decay looks like. This way, she was able to finely characterise the energy level spacings and the quantum numbers characterising each level. s the title of her work suggests, she focused on light nuclei those with an atomic number smaller than 20 (meaning containing at maximum 20 nucleons).

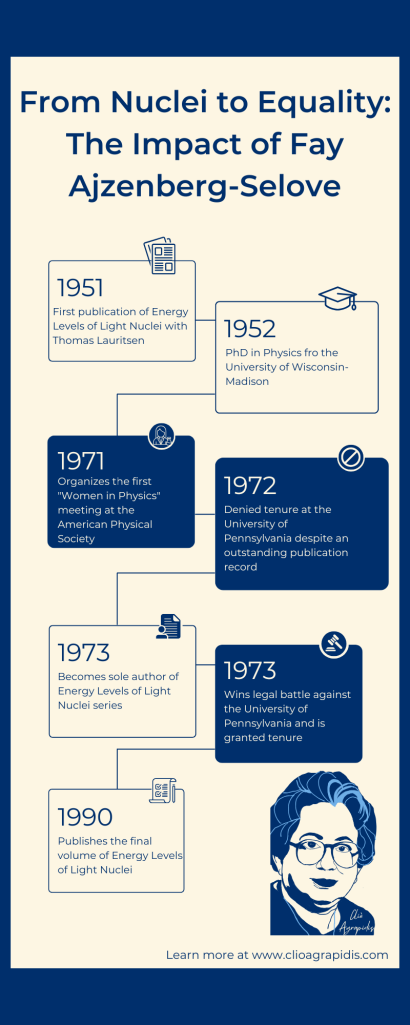

She started publishing her findings in 1951, together with her collaborator Thomas Lauritsen. Starting 1973, she kept publishing Energy Levels of Light Nuclei on her own, until 1990. When she stopped, she had published 26 such compilations of information on the state of the art knowledge on light nuclei and their energy levels.

These immense work is often referred to as the nuclear scientists’ bible, providing critical information on nuclear structure and decay of nuclei with atomic mass numbers from 5 to 20. By providing such a solid and updated foundation on light nuclei, Ajzenberg-Selove defined a whole branch of nuclear physics and supported further developments in the field. Her work allowed researchers to easily find and access data from one single reliable source. Moreover, it highlighted gaps and inconsistencies in the field, leading research in the required directions to fill or resolve those issues. Besides the specificity of nuclear physics research, her research had applications in astrophysics, in particular in stellar nucleosynthesis, the way stars create nucleus in the internal reaction occurring in burning stars, and carbon dating, a widely used methods for dating archeological discoveries.

I decided well there’s Marie Curie, so that I knew that at least one woman could make it.

Fay Ajzenberg-Selove

The Struggle for Recognition in Academia

Having started publishing these compilations and having completed her PhD, Ajzenberg-Selove applied for an associate professor position at Boston University, which would have allowed her to keep working at MIT laboratories. After having received an offer from the faculty chairman, she saw it reduced by 15% on behalf of the Dean. Having learned this decrease in her salary was due to the dean finding out she was a woman physicist, she refused to accept the position unless the initial offer would be restored. Her determination paid off, and the dean relented back to her initial salary offer. However, she had experienced first-hand the inherent sexism lingering in the academic environment.

While in Boston, she also met her future husband. Under the advice of her friend Marietta Bohr, she attended a lecture by Walter Selove and, according to her recounts, immediately fell in love. They got married in December 1955 and ended up building a successful dual-career. Selove, an experimental physicist, went on to discover a meson that he named the f-meson, also called the faon among their friends, in honor of his wife. If you ask me, this is one of the most romantic acts a physicist could ever perform.

Fighting for Equality: The Push for Tenure

Ajzenberg-Selove’s encounters with academic discrimination based on gender were not over. In 1972, she applied for a tenure position at the University of Pennsylvania, where Selove had been teaching since 1957. She was confident in being a strong candidate and was particularly disappointed and surprised when the hiring committee argued that she did not possess a strong enough publication record and, hence, she would not be offered a position. At the time, she was only 46 and had a higher citation count than all member fo the department excluding the Nobel-winner J. Robert Schrieffer. Just months later, she was elected chair of the nuclear division of the American Physical Society.

Not wanting to give in to blatant gender-based discrimination in the hiring process, Ajzenberg-Selove used the above arguments to file complaints against the University of Pennsylvania with both the Federal Equal Opportunity Commission and the Pennsylvania Human Relations Commission. She was successful, and was consequently offered a tenured professorship in 1973.

Mentorship and Advocacy for Women in Physics

Fay Ajzenberg-Selove fought hard against gender discrimination during her professional life. She went on to mentor several students and recalled being excited about seeing more female students joining her classes and how they often ended up being in the group of top-performers. In 1971, she organised the first ever meeting on “Women in Physics” at the American Physical Society annual conference, opening up the path to women becoming officers of the society.

As she wrote in her own memoir, A matter of choices: Memoirs of a female physicist, she had “a wonderful life.”

Leave a comment