Being a physicist means looking at the world with a new set of eyes. And that’s true on holiday as well.

A Windy Day in Skopelos

Yesterday was a windy day in Skopelos. The outer sea was so rough that no ship arrived at the port until the evening, when waters had finally settled and only a light breeze remained.

Rough seas meant no beach for me all day, as it was no condition for a mom-and-toddler (plus nonna) group. I still enjoyed my time by going to a mani-pedi appointment while my mom kept my son busy.

A Rare Glimpse of Solitons

As I walked back uphill to our holiday home, I caught a glimpse of the gulf—and what did I see? A soliton wave! Followed by another one! I could barely believe it.

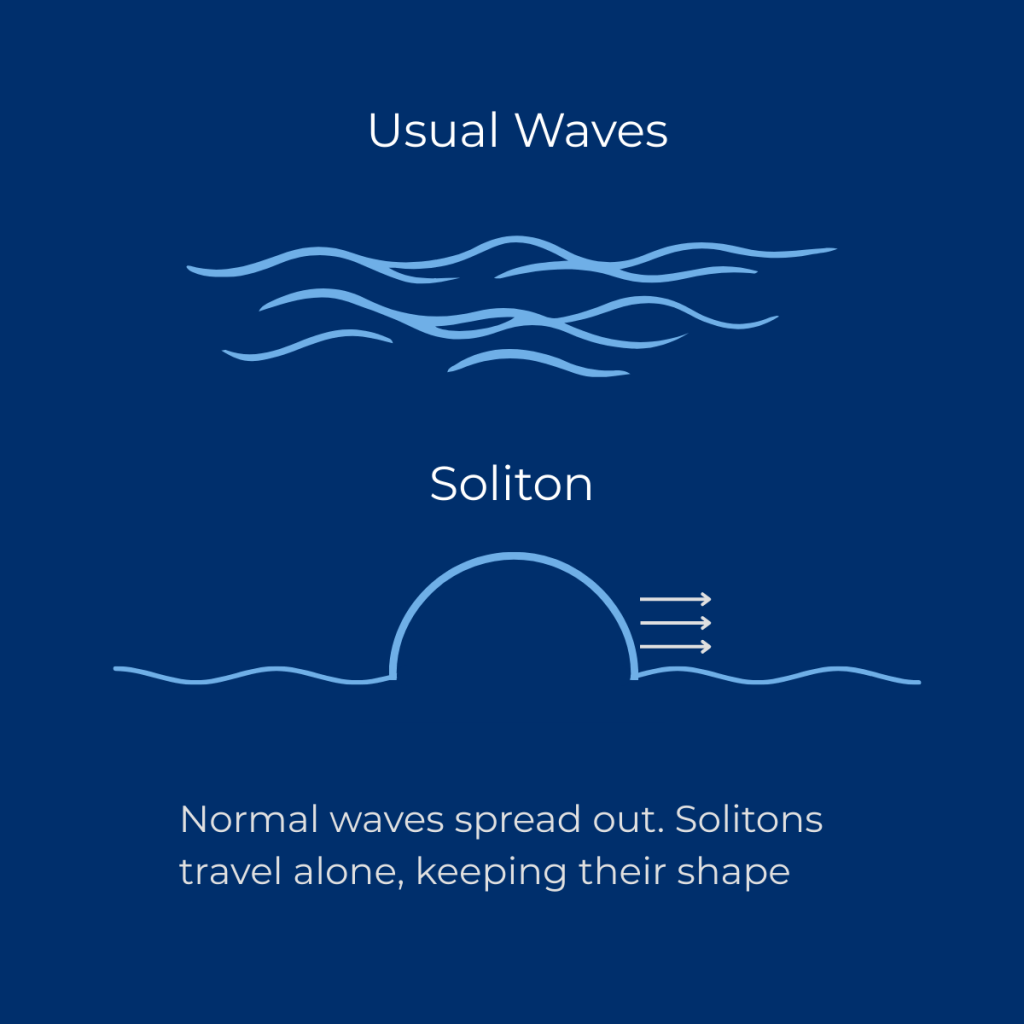

Solitons have a clear appearance, looking like clean, smooth lumps of water traveling by themselves without fading or changing shape. This makes them easy to distinguish from usual waves. Still, I was surprised and, frankly, unsure: can solitons appear in open waters too? Every time I had heard of them, they were mostly cited in the context of canals and rivers.

The First Soliton Ever Spotted

This could also be due to the story of how solitons were first noticed. In 1834, John Scott Russell witnessed and reported the formation of such singular waves while observing a horse-drawn boat. The vessel suddenly stopped, but the water around it did not, forming what he described as “a large solitary elevation, a rounded, smooth and well-defined heap of water, which continued its course along the channel apparently without change of form or diminution of speed.” He followed this heap on horseback for about two miles and called it a Wave of Translation.

This phenomenon fascinated him so much that he ended up setting up a lab at home to reproduce and study these waves. His observations seemed at odds with anything known about hydrodynamics until then. Names like Bernoulli and Stokes had issues accepting Scott Russell’s experimental reports.

From Curiosity to Theory

More reports of soliton experiments came in from France in the second half of the 19th century, but only in 1895 did we have an equation allowing for such solutions: the Korteweg–de Vries equation. Demonstrations of soliton behavior in media governed by this equation became possible much later, in 1965, thanks to computational methods.

Solitons appear as solutions in different branches of physics and mathematical physics.

Hard-to-share excitement

With this (long) preamble, I hope it is clearer why I got so excited about seeing two solitons in the harbor area of Skopelos. So thrilled, I had to tell my mom and my uncle, who both looked at me as if I had just made up a word.

Luckily, my physicist husband was as excited as me when I texted him about it.

Solitons in Open Waters

So, here is a short breakdown of how solitons can form in open waters:

For such a self-preserving wave to form, you need some very specific ingredients:

- Nonlinear wave propagation – the wave’s amplitude affects its speed.

- Shallow water relative to the wavelength – this keeps the wave from dispersing.

- A disturbance to trigger the wave – tides, currents interacting with underwater topography, and the like.

You usually find these conditions in rivers and canals, which offer:

- Uniform depth and narrow width, letting the disturbance create a wave that doesn’t spread sideways.

- Repeated triggers, like boat traffic or sluice gates, which make solitons easier to spot.

Perfect conditions for soliton watching

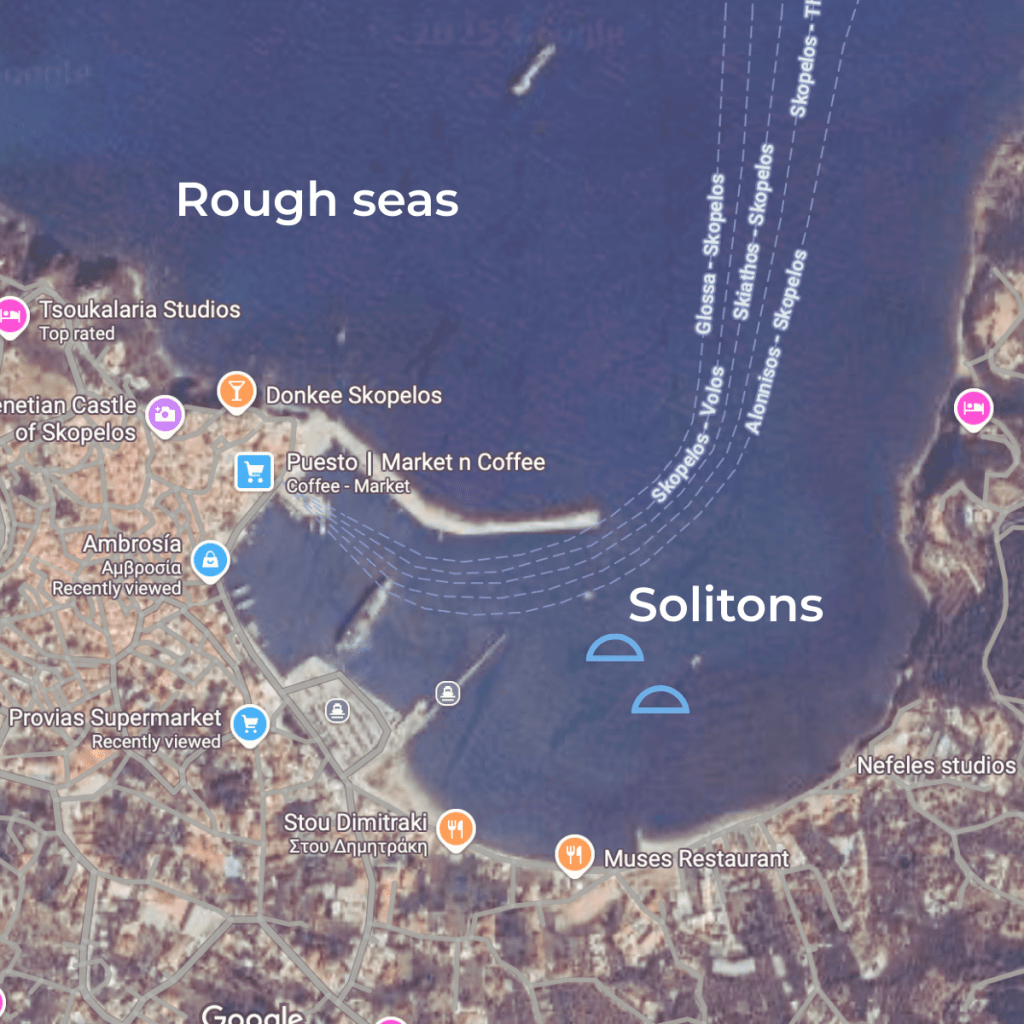

Seeing solitons in open water is rarer, but yesterday’s conditions in Skopelos gulf were perfect:

- Wind-driven currents created fast-moving surface flows.

- Rough seas outside generated waves that entered the gulf, and its confined shape caused wave focusing.

- Shallow bathymetry and stratified layers helped the wave maintain its shape and even allowed for internal solitons that can sometimes be seen at the surface.

Solitons in shallow canals often appear in “soliton trains.” In open water, it’s harder to achieve, but it’s not unusual for a wave to split into two, with a bigger soliton followed by a smaller one—just like the two I saw in the Skopelos harbor.

Too bad I don’t have any pictures. I do, though, have a nice story to share and a bit more physics insight into soliton formation.

Leave a comment